Will a post-QE world sustain the recovery?

Written By:

|

John Arthur |

John Arthur of AllenbridgeEpic examines the impact QE has had on asset valuations, and looks at the knock-on effect it has on emerging markets

When talking about the Iraq war, US Secretary of Defence, Donald Rumsfeld, stated: “Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.”

When I first read this quote I added it to my list of particularly stupid things politicians have said. Increasingly, however, I have found it a useful adage when contemplating asset markets. If you are going to commit money in the hope of making a return, you are taking a risk. It is therefore important to set out the thesis on which you are investing. What do you think you know and what do you think you don’t know?

This way when something happens, it is either something you already knew and therefore is hopefully confirmation of your thesis, or it is information that you were looking for and may therefore either confirm or challenge your thesis. But either way you can now analyse the new information.

There is, of course, a third element as Rumsfeld so eloquently (?) describes. The information that we didn’t know we didn’t know.

So what do we think we know?

We know quantitive easing (QE); the purchase by a central bank of risk assets from commercial banks, is coming to a close (at least for now) in the US and soon in the UK. We know that in Japan, and probably also Europe, the central bank still has the potential to increase the amount of QE in the system. However, this is unlikely to have as great an effect as what we have already seen from the US where QE has been present for the last six years on a previously unimaginable scale.

We know that the at least one of the justifications for QE was to push down the cost of borrowing along the interest rate curve, and to force investors to take on greater levels of risk to achieve the same return (yield).

We can also summarise that because virtually all financial assets have risen in value during the last 6 years whilst the US has undertaken aggressive QE, the policy has worked, investors have been forced into riskier assets. We would appear to have bought forward market returns to the extent that very few assets seem to offer attractive returns commensurate with the level of risk now being taken.

We seem, therefore, to be at a potential turning point, not perhaps in the direction of asset markets, but more fundamentally, in how they work and correlate with each other. QE has been such an irresistible force for nearly 6 years that it has floated all boats. If we look at equity markets since QE started, most markets have gone up faster than corporate earnings. This means that valuations have increased and shares become more expensive.

So, as the US Federal Reserve winds down its experiment with unorthodox monetary policy, what will happen when they begin to shrink their monetary base? So far, the communication to investors by the US central bank has, to me, been very successful. After an initial sell off when markets first focused on this issue, investors have been remarkably calm. Government bond yields in the US have seen increased volatility but we have seen no major panic. This is perhaps helped by the Bank of Japan increasing its QE just as the US finished theirs, and investors’ expectation that the EU will have to commit to real QE to battle what appears to be an economy flirting with deflation.

But as the flow of new money via QE decreases, so the tide that floated all boats must begin to turn. Simplistically, the last 6 years have been about one trade: risk on or risk off. When investors have been confident that the central banks’ policies to pull the global economy out of the post-2008 recession and battle deflation will be successful, all assets have risen in price and investors have increased the risk in their portfolios. As soon as Investors, en masse, question this premise, all risk assets have been sold. Correlations have remained broadly positive across asset classes.

My personal expectation is that the next few years will see investors, once again, concentrate on valuation and investment fundamentals. This should lead to a greater dispersion of returns. It may even mark a period when the average active manager outperforms their index for a period of time, but maybe that is asking too much!

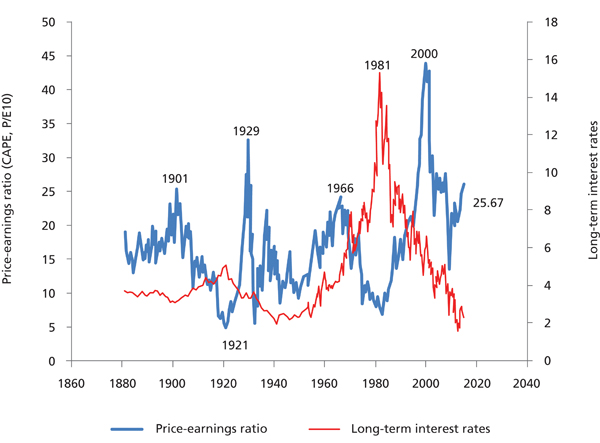

Figure 1: S&P 500 Shiller P/E versus long term US interest rates

Source: Robert Shiller – Yale

Figure 1 shows the cyclically adjusted P/E (CAPE) for the US market. It uses 10-year data to average out the economic cycle and compares this to long-term interest rates. Valuations in the US market appear to rise when investors believe interest rates will fall in the future but valuations do not fall immediately interest rates start to rise. Is this perhaps because markets can tolerate gently-rising rates if they believe the underlying economies are under control and the central banks are acting appropriately?

In Figure 2 you can see that market valuations, as measured by the CAPE, looks high in the US. In addition, US corporate margins are at all time highs. Add to that the assumption that long-term interest rates are unlikely to fall further, and it could be difficult for the US market to push much higher without real earnings growth. This does not mean markets will collapse. It merely suggests that market returns in the US could be low into the future as earnings growth catches up with valuations. This would seem to chime with the idea that QE has forced all assets higher, and potentially brought forward future returns.

Going back to Mr Rumsfeld, we know that the scale of QE on a global basis is reducing. We know that the economic recovery has been slow in many parts of the world. Of the developed world, only the US and UK appear to be in the midst of a self-sustaining economic recovery, and when you scratch under the surface you can easily become concerned about how self-sustaining these recoveries are.

Emerging markets

But all these issues are global: what about emerging markets? I find myself constantly asking: “is now the time to invest in emerging market equities?” I will confess, I do accept the long-term story of high economic growth and a surging middle class (by which we imply disposable income) within emerging economies. The question is will that translate into higher share prices? What are the risks?

The main concern appears to be that traditionally, emerging market equities have risen most strongly when global liquidity is at its most plentiful. In the past, many emerging economies have relied on foreign investment to balance their current account deficit. Will the reduction in the scale of QE and therefore, one assumes, global liquidity, destabilise these economies? This is a known unknown. But many emerging economies are much stronger financially than in the past. Similarly, not all emerging economies are net producers of hard commodities where prices have been falling.

We have other known unknowns which are perhaps more focused within emerging markets yet could have a potentially global impact: ebola, Russian political power, Isis and a destabilised Middle East, the Chinese housing bubble bursting, and high levels of investment in unproductive assets.

All these are areas where I continue to actively seek information and analysis but as known unknowns, they are at least partially discounted by the markets. Any further downside on these issues is because new data points are more negative than we have currently discounted.

But, as a long-term investor, I still prefer to buy assets which look cheap against their long-term history, and I find that draws me to emerging market equities at a time when I see little value in many other asset classes.

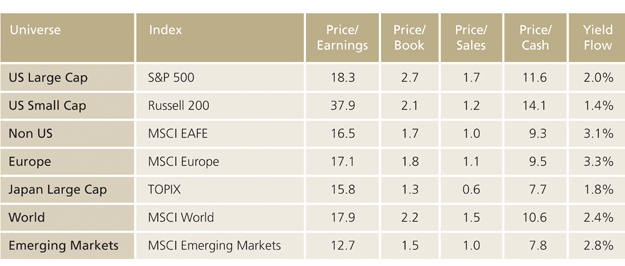

Figure 2: World equity market valuations – 30/09/2014

Source: Acadian Asset Management

Figure 2 gives a number of valuation metrics for broad geographic indices. This shows that generally emerging markets are cheap relative to other equity markets. This in itself is not uncommon, but if I am right and in a post QE world, valuation will matter, then maybe we need to plan for a future which is different from our experience of the last few years.

And what of the unknown unknowns? Well we will just have to wait and see and hope to be able to analyse the events when they happen because they surely will!

More Related Content...

|

|

|