What this year’s M&A boom means for credit

Written By:

|

Andrew Swan |

|

Richard Ryan |

|

Dan Gardner |

With new mergers and acquisitions (M&A) activity at its highest since 2007, Andrew Swan asked senior fixed income fund managers Dan Gardner and Richard Ryan, who manage M&G’s leveraged loan and multi-credit portfolios respectively, what this may mean for different fixed income markets

Andrew Swan (AS): Dan, given that loans exist primarily to finance mergers and acquisitions, this boom in M&A-related activity must have a direct impact on your market?

Dan Gardner (DG): Yes – it does. Aside from the fact that M&A is one of the reasons why loans exist, more M&A activity expands my investible universe, providing me with additional opportunities.

AS: Before delving deeper – why is this boom happening?

Richard Ryan (RR): It’s a result of equity markets rising despite no meaningful increases in companies’ revenues or earnings. Now company managements are under pressure to justify those higher equity prices by improving their income. There are three main ways companies can do this: grow their businesses organically, increase leverage (which includes buying back shares) or the third option, M&A.

DG: M&A activity is ever-present but it goes through waves of very heavy activity, because one high-profile deal can often become a catalyst for several in the same sector.

AS: Are low interest rates also a reason we’re seeing so many deals?

DG: Absolutely. Although credit spreads are not at their most expensive, overall interest rates are so low that a “BB-rated” company can get 10-year debt to finance an acquisition at a 5% interest rate. If they manage to buy the right company, that can really boost shareholder returns. As a result, finance directors are completely alive to the opportunities that low rates provide.

RR: Yes and also, unlike today, some companies previously would have been dissuaded from M&A activity by the threat of a credit downgrade. But several issuers have recently been downgraded to high yield (ie their rating has fallen below BBB) without being punished by debt investors. With the spread differentials between high yield and investment grade at some of the narrowest levels in several years, why wouldn’t a company take advantage?

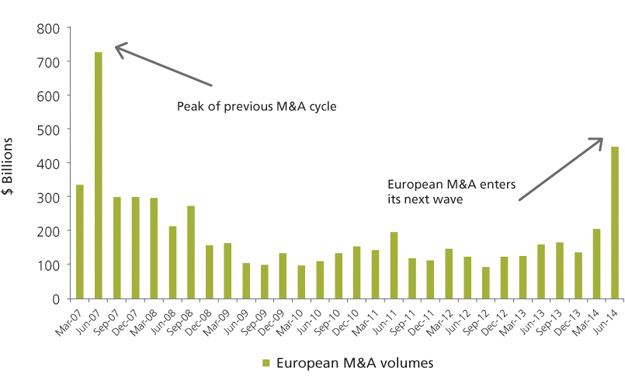

Figure 1: New wave of M&A hits European markets – what does it mean for fixed income?

Source: Bloomberg: June 2014

AS: OK Dan, getting back to your market. How much of this activity is actually being financed in the leveraged loan market? Surely it won’t be unless it’s private equity-related?

DG: That’s a good question. There is definitely a lower proportion being financed in the loan market than in previous M&A cycles. Lots of corporates are chasing growth, so there’s at least as much of an incentive for companies to merge with or acquire another company using public sources of finance as there is for a Private Equity (PE) sponsor to finance a takeover.

Regulation has played its part. The rules changed after Kraft’s lengthy takeover of Cadbury in 2010 to make hostile takeovers harder. Look at Pfizer and AstraZeneca. As a result, PE activity is lower. Banks, with an eye on their capital ratios, are less likely to finance a risky buy-out.

AS: I think there’s a feeling that M&A activity is bad for investment grade credit? Is that justified?

RR: In the vast majority of cases, no. When investment grade companies engage in M&A, they mostly remain investment grade afterwards, so the performance impact is minimal.

But in the minority of cases, you can see a significant impact. If a high-quality issuer takes over a low-quality issuer, greatly improving its credit quality, that would be a very positive outcome. On the other hand, if a highly leveraged PE sponsor takes over an investment-grade issuer, then that could be very negative for the bondholder – because the bonds have suddenly become a lot riskier.

In those instances, there is more to lose than there is to gain for managers running portfolios relative to a benchmark. Contrary to popular belief, “avoiding the losers” is unlikely to generate significant outperformance because each issuer makes up such a small portion of the benchmark. However, as portfolios tend to be far more concentrated than benchmarks, failing to avoid the losers can be costly.

DG: But even given the scenario you described where a PE firm takes over an investment-grade issuer, can’t you protect yourself with covenants? Have the lessons of the last boom in leveraged buy-outs (LBOs) been learnt? Or are “change of control” covenants not generally available in investment-grade bonds?

RR: Covenant protection is variable in investment grade bonds. Morrison’s, which has faced speculation as an LBO target, is a good example. Two of its bonds feature “change of control” covenants, giving bondholders the flexibility to sell the bonds back to the issuer, and the others do not. The performance of the bonds was therefore radically different. Covenants go through cycles in the investment-grade market. When the balance of power leans more towards the investors, you see stronger covenants. Right now, you’re seeing covenants start to slip away.

Figure 2: Morrisons bonds with different covenants react differently to takeover speculation

Source: Bloomberg: June 2014

AS: Richard, what general approach do you take to the investment-grade market during periods of high activity?

RR: Covenants are certainly an important consideration. For example, if two almost identical bonds are trading similarly but one is covenanted and the other isn’t, between the two you should definitely own the covenanted one. Why not take the free protection?

Just as important is the volatility that M&A activity can create. As markets start anticipating changes in structure, leverage and credit quality, we look for areas where the market has over-reacted and then aim to profit from that volatility.

AS: After Pfizer failed to buy AstraZeneca, were the bonds volatile?

RR: No, they were very stable actually. Both are at the high end of the investment-grade scale, the pharmaceutical sector is of course very defensive, and the top players’ balance sheets are super strong. So M&A activity doesn’t always increase volatility or have the type of effect on the investment-grade market that some people expect.

AS: A last word on covenants, Dan. Is it much more of a given that you get strong covenant packages in the leveraged loan market?

DG: It is, but nothing exists in a vacuum. Investors need to be diligent because this is where I think pressure might build. In the last M&A boom, we saw credit spreads widen and covenant packages soften. In this boom, because of the shape of the yield curve, I don’t think we’ll see the former but we are starting to see the latter.

In the high-yield market (and not the loan) market you sometimes come across “portable capital structures”. This essentially means that if the company gets taken over, your issuer can have different leverage metrics than it had when you originally loaned to it, and you have no protection against that whatsoever.

Now, this violates what I consider to be one of the canons of lending: “know who you are lending to”, not just now but in the future. If the issuer I’ve loaned to gets acquired then I no longer know who I’ve loaned to. So, it’s absolutely fundamental that I have the right to take my bond or loan back.

AS: Is there anything else that marks this M&A cycle out from the previous one?

RR: You’re seeing more companies divest entire business units, like the industrial company, Finmeccanica, that sold its train business. It’s much easier to buy an arm of a company than the whole thing because you negotiate directly with the company rather than with thousands of equity holders under public market laws.

DG: For me, that’s where I get the best deals. It’s not necessarily the whole company I want to finance. What helps my market is when big companies come together and divisions get sold off. Those divisions won’t be eligible to borrow in the public markets, so I have less competition. With the information we also get as a private lender, we are well placed to assess the security of the company.

AS: Is there any point in trying to forecast who might take over who?

DG: It’s not worth the effort; you’d have to be plain lucky or simply an insider. But sector by sector there are some warning signals you can watch out for. You can observe for example that growth is tapering off in the pharmaceutical sector but that the companies are awash with cash and obviously they’ll be under pressure to deploy it.

RR: Some industries may be more prone to activity than others, like the telecoms sector, for example.

DG: In sectors like telecoms you can almost get a domino effect. A big deal, particularly if it’s a European firm buying a UK firm, can cause the rest of the industry to become paranoid that the acquirer wants to build a pan-European network. This can force other telecoms companies to merge with each other almost as a knee-jerk reaction. It’s another example of why this type of activity has always happened in waves.

AS: Richard, would a buy-and-maintain or smart beta-style approach help mitigate any of the M&A-related issues that you’ve highlighted?

RR: No. Smart beta approaches tend to ignore valuations. If you buy a bond with a value cushion built into it, then you’ll have some protection against a negative event, whether it’s M&A activity or something like the BP oil spill. Using that as an example, BP had a balance sheet that proved to be bullet proof, but before the oil spill there was no value cushion built into its spread. Although it was a financially robust company, it fell 20% in price before recovering. Those active managers who only owned BP after the sell-off were overcompensated for the risks. We firmly believe that investors should take an active approach to this market.

AS: Thank you for those interesting insights in the midst of this heavy wave of M&A activity. It will be interesting to see how opportunities across leveraged loans and investment grade credit will continue to develop.

More Related Content...

|

|

|