|

Mike Richardson Member of The Society of Pension Professionals Public Sector Committee, and Head of LCP’s Social Housing Practice |

The six sins of smart beta

Written By:

|

Jason Williams |

Jason Williams of Lazard Asset Management lists six risks of which investors should be aware when making smart-beta allocations

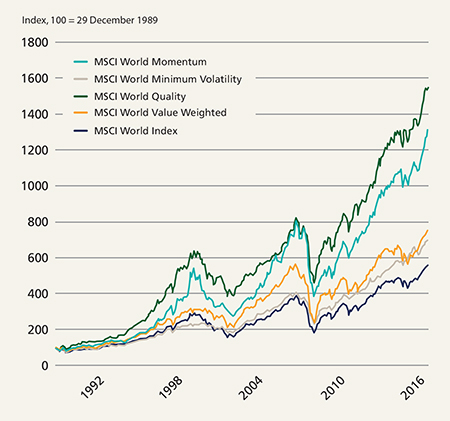

Smart beta funds, often heralded as a new frontier in passive investing, have rapidly grown in popularity over the past several years, with investors seeking to access persistent drivers of returns in an efficient and low-cost way. Smart-beta strategies tend to closely mirror benchmark indices, but seek to generate above-market returns by weighting stock positions differently based on certain factors. Broadly speaking, investors have been attracted by the outperformance of valuation, momentum, quality, and low-risk investment styles (Figure 1) that typically arise from investors’ behavioural biases. Such strategies tend to employ a long-only, single-factor approach within a single asset class, typically equities, and are systematically implemented and rebalanced to maintain the factor exposure.

Academic studies have shown that consistent anomalies persist in the market owing to how investors price certain stocks. Smart-beta strategies seek to exploit these anomalies in order to outperform the broader market, and have amassed a strong following as investors try to capture this “low hanging fruit”.

For more than a decade, capital has principally been allocated to value and low-volatility products. More recently, there has been a proliferation of smart-beta products targeting, among others, momentum, quality, income/yield and size exposures. This has led to a sharp rise in assets invested in an expanding universe of smart-beta exchange-traded funds.

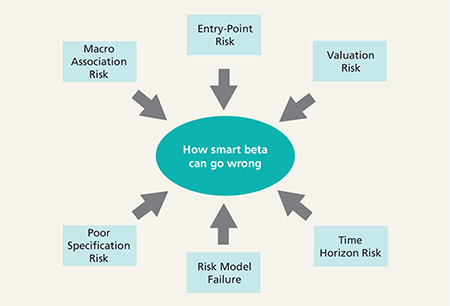

Here we look at six specific risks (Figure 1) that could undermine a smart-beta strategy and detail the environments in which particular smart-beta strategies are more likely to underperform.

Figure 1: Six sins of smart beta

For illustrative purposes only.

Source: Lazard Asset Management

Entry-point risk

The point at which a smart-beta product is adopted is critical. Entry-point risk can have a marked impact on returns when investing in a momentum strategy which, in its simplest form, entails buying companies that have performed well and selling companies that have performed poorly.

Active returns from a momentum factor tend to be above zero for long periods. However, episodic “momentum crashes” that deliver substantial drawdowns do occur. If an investor allocated capital to a momentum strategy just before one of these crashes, they would likely be shocked by the severity of the underperformance. Interestingly, these “crashes” are not entirely random in nature.

Momentum crashes tend to occur when the correlation of returns to high-risk stocks and returns to momentum are extreme and negative. These are times when investors shun high-risk stocks. At this point, momentum stocks carry an extreme beta discount to the market as investors become highly risk averse, strongly preferring stocks that offer better downside protection. What typically follows is a sharp reversal of risk aversion and a sudden change of leadership in the market, resulting in a market shake-out for momentum investors.

Valuation risk

Valuation risk can broadly be defined as the risk of an investor buying an expensive portfolio, in effect locking in poor future returns.

Over the past two decades, returns from quality – as measured by the MSCI Quality Index – have been extraordinary in relation to other popular factors (Figure 2). This quality bias has pushed valuations of high-quality companies to levels rarely seen in the past. Rising valuations suggest that expected returns from investing in high-quality companies in general are likely to be significantly eroded.

Figure 2: Smart-beta factors capture market anomalies to drive outperformance

As at 31 July 2017

Source: MSCI

Time horizon risk

Time horizon risk is the risk of a prolonged drawdown. This risk occurs when an investment is made in a smart-beta vehicle at a time when the economic environment is not conducive to that particular style of investment. Consequently, an investor may face the difficult decision of whether to maintain or abandon a single-factor strategy that has, up until then, a history of success.

Risk model failure

A frequent criticism of quantitative investment approaches is their use of, and reliance on, risk models. Concerns are usually centred on risk models’ reliance on:

- Controlling macro exposures: This often introduces trades that are risk driven rather than return driven, making the portfolio and its construction less transparent and more difficult to understand

- Backward-looking data to build forward-looking forecasts: The reliance on historic data to calibrate exposure to macro factors, in both fundamental and statistical models, could give incorrect signals and underestimate risk

While the approach employed by risk models to calibrating and measuring stock risk is highly effective in most market environments, there are instances where these models fail. Risk model failure is important to understand as it could result in the underestimation of a portfolio’s exposure to a sudden reversal of a particular macro risk factor, or an oversized stock position that does not reflect the stock’s inherent risk.

Poor specification risk

Specification risk captures the importance of the investment metrics an investor uses to represent a factor exposure. Using different investment metrics can lead not only to differing patterns of returns, but also significantly different levels of alpha generation. Choosing just a selection of value metrics that have historically performed the strongest is not necessarily the best route to constructing a robust and desirable value factor.

Defining and combining investment metrics should involve, among a number of important considerations, an in-depth analysis rooted in robust processes that fully appreciates:

- The investment nuances of the ratio or metric

- The reliability and consistency of the pattern of returns it offers

- Its association with macro risk

- Its upside/downside capture

Macro association risk

Macro association risk has become particularly prominent in the post-financial crisis era and can be defined as the impact of a macro outcome on factor or style performance. The correlation between factor returns and macro risk has risen while the alpha opportunity has often been compressed, perhaps as a rising level of capital has chased after similar factors. Equally, this relationship between factor returns and macro risk could be the result of the current regime of unconventional monetary policy, where economic fragility and stretched central bank balance sheets have conspired to tie stock returns more closely to macro risks. However, we believe that macro association risk can be managed, mitigated, or even neutralised, by adopting a more sophisticated approach to factor investing. The key is to understand where the risks are and how to manage them accordingly.

Conclusion

We believe it is important for investors to be aware of the ways that smart-beta allocations could potentially lead to disappointing returns. In our view, smart-beta investing is far from being a small step in the evolution of passive investing, despite that typically being an investor’s perception. The pursuit of generating consistent returns from investment anomalies entails significant research, market experience, and risk management expertise. When researching a naïve smartbeta strategy, evaluating the six risks we discuss could help an asset allocator move forward with greater confidence.

More Related Content...

|

|

|