The case for private equity impact investing

Written By:

|

Maggie Loo |

Maggie Loo of Bridges Ventures explains how a focus on improved social and environmental outcomes can help investors find growth and value

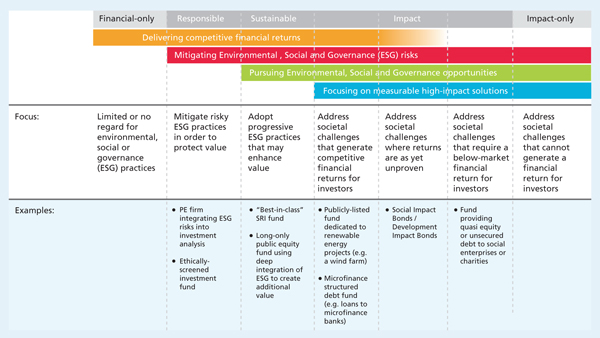

Most institutional investors now accept that embracing responsible investment principles helps to mitigate environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks across their equities portfolio – and thus protects value. Many investors also now recognise that working to improve ESG practices (the principle behind sustainable investment) can increase the value of their portfolio over time. A company with best-in-class ESG practices will typically be more attractive and more valuable than a competitor with sub-standard ESG practices. In the last few years, we’ve also seen a significant growth of interest in impact investing – which focuses on funding investable solutions to some of our biggest social and environmental challenges.

The most recent figures from Eurosif (the European Sustainable Investment Forum) suggested that sustainable investment increased by almost 23% between 2011 and 2013, well ahead of the market as a whole – while impact investing was up 132% during the same period (albeit from a low base). As a fund manager that has been operating in this area and talking to local authorities about it since 2002, Bridges has experienced this first-hand: local authority pension funds (along with many other institutions) are now much more inclined to consider allocating a portion of their portfolio to impact strategies, usually via specialist intermediaries.

So why this surge in interest? Strong policy support from central government has been one factor. During the UK’s presidency of the G8 in 2013, then-Prime Minister David Cameron, established a taskforce on social impact investment, chaired by Sir Ronald Cohen, to gather input from practitioners around the world (this has since evolved to become a global steering group, with a national advisory board established to lead the conversation at a UK level). Government has also supported the establishment of the first social investment bank (Big Society Capital), introduced tax reliefs for social investment, and provided funding for a number of social impact bond programmes (of which more later).

More broadly, however, the rising interest reflects the attractiveness of the premise behind impact investing: that by responding to a long-term societal trend or addressing a far-reaching societal problem, it’s possible to generate both positive impact and attractive financial returns.

Figure 1: Spectrum of capital – how impact investing fits into the broader investment universe

Source: Bridges Ventures

Impact as a value driver

There is still some scepticism among fiduciaries and advisers (particularly within private equity) about the idea that investors can “have their cake and eat it.” But the evidence is mounting that using impact as a lens can be a way to find growth and value in a crowded marketplace – and thus deliver strong returns over time.

For instance: investment in regeneration areas has a tangible impact on local communities – by providing affordable housing or SME business space or communal amenities, for example. However, it also offers investors the potential for long-term value growth (Bridges bought the Hoxton Hotel at a time when its local borough was classed as one of the most deprived in the country; eight years later we were able to sell it for nearly nine times our original investment).

On the environmental side: a significant portion of the UK’s carbon emissions come from its existing building stock (over 40%, according to one government estimate). So refurbishing office buildings to incorporate positive environmental features can go a long way towards reducing our carbon footprint. But it also makes the offices more attractive to tenants, because it reduces their bills – which typically results in better occupancy rates and rental yields over time.

Similarly, businesses that are supporting underserved populations or responding to demographic shifts – perhaps through the provision of better healthcare services or training courses or care home places, for example – are not only helping to solve a big societal problem; they are also potentially opening up a large new addressable market. For instance, of the 424,000 members who have signed up to The Gym (the low-cost health and fitness business we launched in 2008), a third had never been members of a gym before.

There are an increasing number of businesses like this who reject the idea that there has to be a trade-off between financial returns and societal impact. Instead, they see impact as a long-term value driver, helping them to build stronger relationships with their customers and stakeholders.

The investment case

For local authority pension funds, this creates an interesting opportunity. Sustainable or impact investment can help to support the regeneration of underserved areas locally, potentially “crowding in” private investment alongside public money. It can also help local authorities to tackle social problems in a way that will benefit other areas of public spending.

One obvious example of this is social impact bonds, whereby the local authority (often with central government support) commissions social sector organisations to deliver a programme for an at-risk group – such as children in care homes, or young people on the verge of dropping out of education, or adults with long-term health conditions – and pays them according to how successful they are in delivering better outcomes. By investing in these early interventions, government can save money in the longer term (through reduced healthcare or welfare costs, for example).

Nor do local authority pension fund CIOs necessarily have to compromise on performance. Although many impact fund managers are still relatively new and have relatively short track records (compared to traditional private equity funds), performance figures to date look promising. According to Cambridge Associates’ Impact Investing Benchmark, for example, impact funds launched between 1998 and 2010 that raised under $100 million have returned a net IRR of 9.5% to investors, easily outperforming similar-sized funds in the standard private equity universe (4.5%).

Even if there’s a chance that some financial trade-off may be required for the sake of impact – which could be the case with a nascent area like social impact bonds – there’s a good argument that these investments will be less correlated to the broader economy, because the issues being addressed are typically non-cyclical. So there may be a diversification benefit to including them as part of a balanced portfolio.

Moreover, according to an illustrative sample portfolio constructed by a working group of the G8 Taskforce, an investor with a carefully-selected impact investment allocation of 8-12% – even if they do impact deals that on average require a 20% “haircut” on financial returns (relative to traditional products within the same asset class) – should be able to achieve the same portfolio-level financial return as an investor with no impact allocation, without significantly increased volatility. The proviso is that the investor must be willing to accept a larger share of illiquid investments; an approach that may be well suited to local authority pension funds who can take a long-term view.

More work on portfolio construction is still required. But if it turns out that an impact allocation can improve a portfolio’s risk-adjusted financial returns while also delivering positive social and/or environmental impact, that should be a powerful driver of asset allocation decisions over time.

Pooling resources

What’s also clear is that the move towards pooling will make it easier for local authorities to allocate to sustainable and impact investing. Over the years we have been fortunate enough to build some strong relationships with a number of local authority pension funds, who have supported us across a number of different vehicles. However, when we started raising our latest UK property investment vehicle, the level of collaboration between these pension funds was much greater than ever before: they were able to share information, coordinate due diligence and conduct some of the negotiations as a bloc. As a result, the process was much faster, cheaper and more efficient than it would otherwise have been, allowing us to reach a £168 million first close in just three months (a significant boon at a time when we had a number of live investment opportunities).

This level of collaboration was only possible because of the closer relationships fostered by recent pooling discussions. So the move towards pooling – notwithstanding its various practical challenges for local authority pension funds – does at least bode well for nascent or specialist areas like private equity impact investing. By improving collaboration between pension funds, it will enable much more sharing of expertise and data, allowing newcomers to get up the learning curve faster by utilising the insight and experience of those more familiar with the area.

Over time, our hope is that this greater level of expertise, coupled with strong policy support and a growing supply of investable opportunities, will enable more local authority pension funds (and other institutional investors) to allocate to impact. The UK still faces a number of social and environmental challenges so large and complex that they can only be addressed if the government, philanthropists and the private sector work together. Impact investing offers a promising avenue to facilitate this.

More Related Content...

|

|

|