Sustainability an essential ingredient for emerging markets investing

Written By:

|

Fabiana Fedeli |

|

Masja Zandbergen |

Fabiana Fedeli and Masja Zandbergen of Robeco discuss why it is important to integrate ESG data into country and stock analysis when considering investments in emerging markets

Sustainability and emerging markets may seem like a contradiction in terms, given the significant environmental, social and governance (ESG) problems that many developing nations face. In fact, it is the very nature of these issues that makes the use of sustainability principles not only advisable when considering investing in emerging markets equity or debt, but essential.

Put simply, the use of ESG factors allows an investor to separate the wheat from the chaff and find some excellent opportunities, as well as places to avoid. It can also be highly profitable: market inefficiencies caused by lower standards of data availability, poor transparency and governance standards, and issues relating to climate change, human rights and product safety standards, are a potential source of alpha for emerging markets investors.

The key to success is embedding sustainability within the core decision-making framework and not viewing it as some sort of add-on afterwards. For the maximum effect, this should ideally be done both on a top-down basis from a macroeconomic and geopolitical perspective, and bottom-up for the securities being considered for an emerging markets portfolio. This requires access to high quality research – and therein lies the real challenge, given the notoriously patchy nature of accurate data from emerging markets.

Structured research and evaluation of sustainability criteria is key to success

So how to go about getting the information? As always, it is best to cast your net as widely as possible, and utilise both internal and external sources. Sources for external data have grown in recent years, with a rising number of independent data providers and sustainability information specialists. We believe the best place to start is from within, creating an in-house database about the available investible universe. A good external source to look for opportunities is among the members of the MSCI Emerging Markets index or the other indices that include companies that are either based in, or extensively serve, this vibrant and diverse space. That makes it relatively easy to create an investible universe and decide which countries, industries or sectors to target.

An investment team should then lay down a framework of the ESG issues to look for, particularly what pertains to their own investment style or philosophy. This should include more obvious topics such as the treatment of external shareholders, board and management quality, financial discipline and supply chain risks, as well as less obvious issues such as pollution for “E”, labour relations for “S” or levels of state control for “G”. Once basic parameters have been established, the net can be cast further afield, both in terms of the numbers and types of companies, and in the complexity of ESG factors used to assess investibility.

The use of scoring systems has become popular, particularly in awarding both negative and positive points, or even in having a “flagging” system where green flags mean something is investible and red flags show companies or sectors to avoid. This is where a top-down approach really comes into its own for emerging markets, since it can be as important to take a view on the country as much as on the companies operating within it. A country with a negative ESG profile due to some of the typical risks associated with emerging markets such as corruption, poor social care or human rights issues, would need to be given a country risk premium. That means it would be penalised in its valuation assessment versus a country with better ESG performance, making relative comparisons possible.

If a company has a poor ESG profile, analysts would have various options open to them to gauge the investment risk from a sustainability perspective. For example, they could adjust the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) in the case of ESG-related concerns. This imposes a higher threshold for holding such a company in portfolio, the investment case will be impacted by a more demanding valuation calculation. WACC adjustments could occur on the back of environmental issues such as deforestation for palm oil production or mining of minerals for use with electric cars and smartphones.

Three things to consider

It is worth noting three things here. Firstly, sustainability investing has long moved on from being an “ethical” crusade, and all investors still have a fiduciary duty to focus on getting the best possible returns for their clients, wherever that may be. Subsequently, ESG analysis should only focus on financially material factors – those metrics that can have an impact on a company’s business model and value drivers such as sales growth or profit margins. This varies per type of company; for example, a sound environmental policy is more material to a mining company than to an insurer. Other input factors can affect a score; for example, if China were to introduce a carbon tax, then the operating cost of a coal-fired independent power producer would increase, making it necessary to reevaluate the security.

Secondly, ESG performance should not be the sole reason to buy or sell a stock, or even be a decisive factor between two individual stocks. It forms part of the mix but is not the whole story; a company could perform well on ESG, but have a terrible business model, or serve a dying industry.

Thirdly, it’s not just about investing: we believe that investors should also utilise active ownership techniques such as engagement and voting to seek improved company behaviour. This is particularly relevant for emerging markets, where poor governance has traditionally been one of the biggest corporate concerns. Put simply, better-behaved companies become more valuable, and continual persuasion through engagement can produce major enhancements further down the line. South Korea has proved to be a good example of how enhanced corporate governance through treating external shareholders more favourably has raised the price-earnings ratios of companies.

Exclusions and the UNPRI’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Even though we believe that ESG integration and active ownership is the best way of addressing ESG issues in emerging markets, we also see that the most widely used option is still that of exclusion. Many investors now follow the guidelines laid down by the United Nations Global Compact and exclude those companies which breach it. Such breaches may relate to human rights, (child) labor standards, or environmental issues that are too great to overcome. These breaches relate to the behavior of companies. Engagement can be a powerful tool for change in these cases. But if a company does not comply, exclusion is the only option. However, when it comes to the products a company makes, engagement cannot really lead to meaningful change. For example, we cannot ask tobacco companies or thermal coal producers to stop making the products they make. So, if these products are deemed detrimental to sustainable development, the decision can be taken to stop investing in those areas.

Another way of implementing sustainability is actually looking for investments in companies that contribute positively to sustainable development. Investors can choose to invest to meet the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and identify those which specifically affect emerging markets. The goals range from ensuring the availability of water and sanitation for all, to food security, achieving gender equality, and enabling access to affordable and sustainable energy – with the aim of meeting all of them before 2030. These are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The United Nations’ SDGs

Source: The UN

It is worth the effort

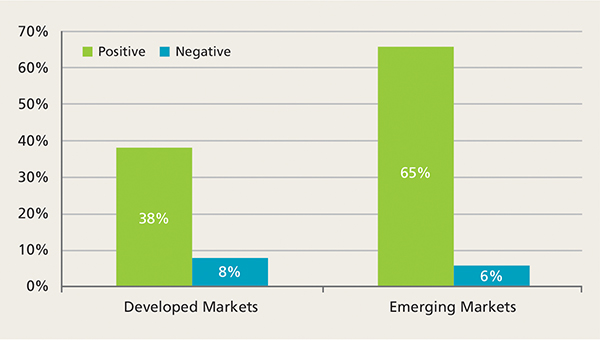

It is certainly worth making all this effort: independent research shows that while adopting ESG factors in developed markets has a positive effect on corporate financial performance in 38% of cases, for emerging markets that positive effect is seen in 65% of cases. This is illustrated in Figure 2. Addressing the governance factor was shown to have the greatest influence.

Figure 2: Relationship between ESG and corporate financial performance

Source: Gunnar Friede, Timo Busch & Alexander Bassen, ‘ESG and financial performance: aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies’, Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment, November 2015.

In conclusion, evaluating financially material ESG factors in an emerging markets investment process offers a win-win; it can limit downside risk and capture upside potential, thereby generating alpha. Taking sustainability integration even further through the use of values-based exclusions or investing following SDGs to create socio-economic impact can exist alongside the ambition of realising financial returns. Nevertheless, while gathering and analysing relevant ESG data is key, integrating ESG data into country and stock analysis is essential. Only then can an investor really determine the true value of an investment opportunity in emerging markets.

More Related Content...

|

|

|