Rethinking infrastructure

Written By:

|

Gregory Smith |

While more institutions are creating separate allocations for infrastructure, capital deployment is lagging behind. Infrastructure pioneer Gregory Smith of InstarAGF Asset Management tells us why….and how investors should be thinking about the asset class

In the early 2000s, I oversaw the establishment of the first private infrastructure fund in Canada, a process that included defining infrastructure as an investment opportunity and educating the market on the merits of these “boring to barely interesting” assets.

Where infrastructure was once the wallflower of the alternative investment space, it now plays a starring role in an increasing number of institutional portfolios. Six years ago, only a quarter of global institutional investors considered infrastructure as a distinct asset class. Today, it is estimated that nearly 60% of global institutional investors have separate allocations for infrastructure, with targets typically ranging between 1 and 10%.

The growing appeal of the infrastructure asset class

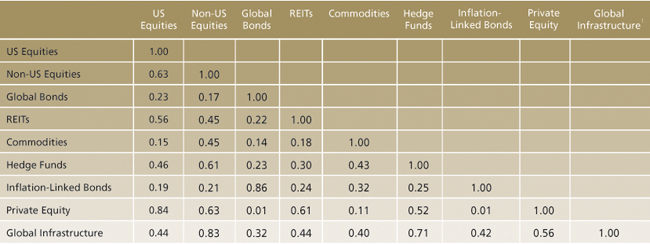

Private infrastructure investment has accelerated in recent years as investors seek real alternatives that are more resilient to economic cycles, have lower correlations with traditional asset classes, offer less volatility, provide some inflation protection, and deliver current yield – which makes infrastructure investments especially attractive in the current interest rate environment.

At the same time, ageing critical infrastructure in North America, the United Kingdom, Europe and elsewhere is fuelling massive demand for capital to maintain and modernise infrastructure and to build for the future. Total annual investment in infrastructure globally is projected to reach $4 trillion by 2017.1

The appetite for infrastructure investment is greater than ever before – and still growing. A study by Preqin suggests that in 2014 institutional investors are more likely to increase allocations to infrastructure than to private equity, hedge funds or real estate, with 46% of investors polled planning to do so.2 Investors are attracted to the infrastructure asset class for its long-term duration and return profile, with a critical mass of evidence suggesting that adding unlisted infrastructure to a portfolio typically delivers diversification benefits, improves return per unit of risk, and enhances overall efficiency.

Figure 1: Infrastructure’s relatively low correlation with other asset classes (July 2000 – March 2010)

1. Macquarie Global Total Return Index

Source: Credit Suisse Asset Management

Obstacles to putting capital to work

While investors are embracing infrastructure as a core component of their asset mix, the actual deployment of capital lags growth in allocations. This dichotomy highlights some of the obstacles – perceived and real – that investors are grappling with in a complex, high-traffic market.

First, robust capital inflows to the sector overall are driving greater competition for certain assets, often resulting in aggressive pricing and higher valuations. But this does not mean there is an oversupply of capital, or too many investors chasing limited opportunities. On the contrary, I believe there are more quality infrastructure investment opportunities available today than ever before, particularly in the mid-market, where dynamics are substantially different than in the market overall. While there will always be examples of mispriced assets, they are more an exception rather than the rule. The challenge for investors is less related to competition and more about matching investments to their own objectives, risk tolerances and areas of expertise.

Although infrastructure is distinct from other asset classes, it is itself a diverse category with both core and non-core assets, the former consisting of assets such as mature utilities, and the latter typically referring to more volume-dependent infrastructure such as sea ports or railways. The risk/return spectrum between these categories varies dramatically and there may be only a subset with the attributes an investor is seeking.

Further, infrastructure assets with the same physical characteristics can represent very different investment opportunities, with the risk/return balance contingent upon the maturity of the asset, geographical and sector diversification, and asset-specific supply and demand drivers. Investors need to understand that infrastructure investments derive their attributes from the contractual relationship that creates the investment opportunity in the first place, and that these investments may have very little value outside of the contract. Accordingly, an asset’s structure is paramount to its return profile.

Some inherent risks of infrastructure are daunting for investors, who may be wary of certain categories or geographies, or the political and regulatory risk surrounding an investment. The tangible socioeconomic footprint of an infrastructure asset, by virtue of the essential services it delivers, makes these risks especially acute, and, without the right risk mitigation mechanisms and experience, a potential minefield. A stable political and regulatory environment is likewise critical to investment returns, with unanticipated changes potentially radically altering an asset’s investment profile, as we have recently seen in the UK water sector.

These obstacles are not insurmountable but they do underline the importance and value of expertise. Investors need to set clear objectives for their infrastructure strategy and stick to them. They need to know their risk tolerances and resist the lure of the siren’s song. And they need to “know what they know and do not know” when it comes to infrastructure category, asset lifecycle and jurisdiction.

Today’s investors have at least one significant advantage over the early movers in the space: they can learn from the lessons acquired at great cost by others, including the importance of conservative assumptions and downside protection.

Choosing the right partner and sweet spot

While more institutions and pension funds are investing directly, it is an arduous undertaking fraught with challenges related to scale, capacity and transactional skill. Finding investment opportunities with the right structure and setting, and then managing them properly to maximise returns requires deep market knowledge and effective risk management. It also takes sophisticated operational know-how to improve how an asset actually runs, which in my experience is the secret to generating significant alpha. For those reasons, investing in unlisted funds with seasoned investment professionals, or as a co-investor alongside a fund, typically provides access to the diversity, quality and returns investors are seeking but at a lower risk than flying solo.

When evaluating a fund manager, investors should seek a clear strategy and flexible mandate that will enable a fund to capitalise on relative value plays in select jurisdictions and within defined infrastructure categories to generate an attractive risk-adjusted return. As a new asset class, market inefficiencies exist, which can create unique investment opportunities. At InstarAGF, for example, we are continuously screening potential investments, which gives us insight into the relative value of different sectors over time. This knowledge enables us to choose sub-sectors and individual investment opportunities that have superior return dynamics relative to the risk profile of the underlying asset.

While megadeals capture the headlines, they often fail to bring home the bacon. It is my experience in over 25 years in the private equity and infrastructure sectors that the size of the transaction is a key determinant of long-term value. To borrow a private equity example, between 1990 and 2011, European all-market private equity IRRs averaged 9.1% compared with the average mid-market private equity return of 17.2%.3 So there is an inverse relationship between the size of the fund and return/risk profiles, a relationship that appears to extend to infrastructure funds.

Indeed, I believe the mid-market infrastructure space, where the enterprise value of assets typically ranges from $100 million to $750 million, offers an extremely compelling value proposition. Notably, at this entry point deals are more likely sourced through relationships as opposed to competitive processes, which allows for flexibility around timing and structuring, enabling you to successfully compete on factors other than price. History suggests that the mid-market typically delivers returns that are 100 to 150 basis points over the returns of the infrastructure market as a whole.

Investment opportunities currently abound in the mid-market space in North America, which, with its vast size, remains a highly attractive market where a significant amount of existing infrastructure is reaching the end of its useful life. This fact, paired with a relatively stable regulatory and legal framework, is enticing capital from both domestic and international investors. Our team is currently seeing a steady deal pipeline with energy, renewables, utilities and transportation all in the mix.

Conclusion

It is inevitable that a wealth of infrastructure opportunities will come to market in the years ahead. An estimated US$57 trillion, or $3.2 trillion per year, is required over the next 30 years simply to keep up with projected growth in gross domestic product.4 Private investment is critical to addressing this staggering infrastructure need. More must be done to unlock this source of capital, a fact recognised in many jurisdictions, including the UK, Europe and North America where governments are increasingly working to remove barriers to institutional investment flows.

Institutional investors are drawn to the infrastructure asset class for its attractive return attributes and power to build wealth for their millions of beneficiaries. But it is also worth remembering that investing in modernising or building infrastructure directly affects productivity and socioeconomic conditions. In the UK, for each £1 billion increase in infrastructure investment, GDP increases by a total of approximately £1.3 billion.5 To put this economic benefit into even more striking terms, numerous studies show that as infrastructure quantity and quality climb, income inequality declines. And the legacy of infrastructure renewal – greener electricity, cleaner water, better public transportation – reverberates for generations.

There’s certainly nothing boring about that.

The name Instar refers to the Instar Group Inc. and its direct subsidiaries. The name AGF refers to AGF Management Limited and its subsidiaries and affiliates. The name InstarAGF refers to InstarAGF Asset Management Inc. and affiliates. This article does not constitute and should not be interpreted as either an investment recommendation or advice, including legal, tax or accounting advice. None of Instar, AGF or InstarAGF guarantees the performance of any fund or the repayment of any capital from a fund or any particular rate of return. The information presented in this article has been obtained from sources that InstarAGF considers to be reliable and is based on present circumstances, market conditions and beliefs. The information contained herein does not purport to be complete. Neither Instar, AGF nor InstarAGF have an obligation to update this article or correct any inaccuracies or omissions therein.

1. Bain & Company, February 2014.

2. “Prequin Investor Outlook: Alternative Assets, H1 2014,” Prequin, 2014.

3. “European Mid-Market Private Equity: Delivering the Goods,” European Private Equity and Venture Capital Association, 2012.

4. “Infrastructure productivity: how to save $1 trillion a year,” McKinsey Global Institute: McKinsey Infrastructure Practice, January 2013.

5. “Securing our economy: the case for infrastructure,” Civil Engineering Contractors Association, May 2013.

More Related Content...

|

|

|