Rethinking fixed income: an alternative approach to emerging markets

Written By:

|

Sherilee Mace |

Emerging market debt is an asset class that is well suited to an absolute return approach. Current market dynamics make discriminating between winners and losers essential, writes Insight Investment’s Sherilee Mace

In recent years many investors have come to recognise the value of absolute return approaches to investing. This has been particularly true in the bond markets. As yields have fallen, freeing managers from traditional benchmark constraints has been one way for pension funds in the LGPS sector to maintain positive contributions from fixed income assets. Absolute return approaches enable managers with skill to express their investment views precisely by looking at both long and short opportunities in an unfettered way.

Insight advocates absolute return approaches to fixed income with the following characteristics:

- Institutional quality governance, investment processes and risk management

- Invests only in best ideas: an absolute return manager should only seek to invest in the ideas with the best risk/return profile, while excluding or potentially adding short exposure to the least attractive

- Focuses on return drivers: identify components of return and take targeted exposures (not just beta)

- Expresses negative views via short positions: short positions provide potential portfolio benefits regardless of market direction and allow portfolio managers access to the broadest opportunity set

- Seeks to preserve capital: avoid large drawdowns by giving managers the flexibility to hold cash. By stressing capital preservation, a portfolio can be constructed which can capture upside when market conditions are favourable and limit the downside when they are not

These principles have been tried and tested in developed bond and credit markets. We believe they are also particularly well suited to emerging market debt (EMD). The debt stock of EMD is now $14 trillion spread across more than 70 countries. These countries do not move in lock-step as a homogeneous block. Emerging markets (EM) economies vary enormously in terms of their size, structural development, rate of economic growth and exposure to external factors both positive and negative.

For example, both Senegal and South Korea are regarded as emerging markets. Senegal has a GDP per capita of around $1000 and exports fish and groundnuts. South Korea’s GDP per capita is $36,000 and it exports market-leading mobile phones and nuclear reactors. The Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland are growing at rates between 4% and 6%. By contrast Russia and Brazil have slipped into recession.

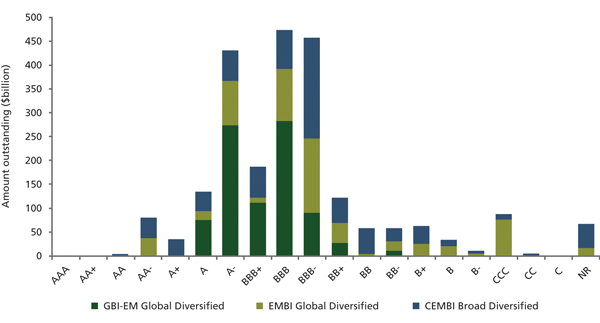

Figure 1: Emerging market debt offers significant diversification

Source: JP Morgan indicies as at February 2015

The diversity of emerging markets is also evident in the development of capital markets and the range of instruments that are available to investors. There are seven sub-asset classes available to investors in the most developed capital markets: external (hard currency) sovereign debt, external corporate debt, local currency denominated government debt, local corporate debt, FX; interest rate swaps, and credit default swaps.

The growth of locally denominated credit is particularly significant. The Asian crisis of the late 1990s revealed how susceptible EM economies with large US-dollar obligations, often combined with unrealistic currency pegs, were to capital outflows and devaluation leading to default. The main local currency benchmark, the JP Morgan GBI index has seen no defaults since its launch in 2002. 93% of the index is rated investment grade with an average rating of BBB.

Timing matters

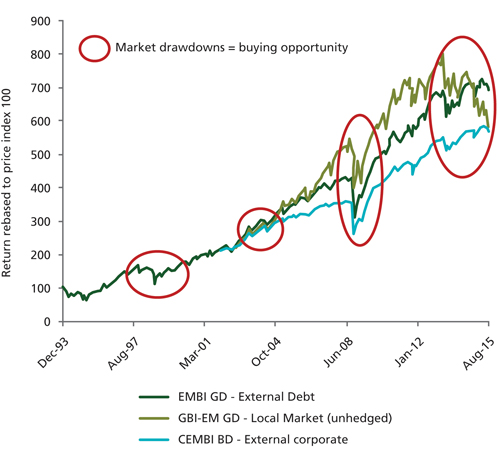

One of the biggest conundrums for investors looking for exposure to the EMD asset class is timing. Significant gains in this asset class have tended to be associated with the aftermath of periods of maximum stress (Figure 2). At the time, these do not look like attractive entry points. The headlines are screaming “crisis” and the narrative surrounding the asset class is overwhelmingly negative. However, waiting until the mood music improves inevitably involves an opportunity cost.

An absolute return approach could help to mitigate the risk of this potentially difficult timing decision. When markets are volatile and sharp drawdowns likely, an absolute return approach can go short. When markets turn they can be nimble enough to capture the upside by adding long exposure. A portfolio that contains both long and short positions with the aim of delivering an absolute return can also preserve capital by holding cash. As volatility subsides, it can deploy that capital opportunistically.

Buying into the asset class in a long-only format at cyclical peaks can coincide with a serious drawdown. As Figure 2 shows, it can take some time for the asset class to regain losses after a sharp cyclical sell-off. EMD has a tendency to be a smooth ride on the way up and a rollercoaster on the way down. Traditional index approaches therefore exhibit risk-adjusted returns that are not compelling.

The time horizon of an absolute return strategy is also different to that of a long-only portfolio. Benchmark-driven strategies will look to outperform an index over the course of a market cycle, which may be between three and five years. An absolute return strategy will seek to deliver positive returns over rolling 12-month periods.

Figure 2: Timing is critical – the best buying opportunities are often during drawdowns

Source: Insight and JPMorgan as at 30 September 2015. CEMBI-BD represents JP Morgan Corporate Emerging Market Bond index – Broad Diversified; GBI-EM GD represents JPMorgan Global Bond Index – Emerging Markets Global Diversified; EMBIGD represents JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Index.

The current outlook

The value of an absolute return approach comes to the fore in volatile markets. EM debt and equity are currently a pariah asset class. According to the Institute of International Finance, net capital flows will turn negative in 2015 for the first time since 1988. Portfolio outflows from emerging market funds have also been unremitting. Bank of America Merrill Lynch has recorded ten consecutive weeks of US mutual fund outflows (to the end of September).

But even against this backdrop of seeming unremitting gloom the picture is nuanced across the asset class. The JP Morgan EMBI+ Index, which measures hard currency (dollar-denominated) sovereign bonds, is in positive territory year-to-date. It is locally denominated debt that has taken the strain. The JP Morgan GBI-EM Index is down 14.5% in US dollar terms (as at 31 September). Positioning does matter. In 2015 the ability to short FX has been a vital tool of capital preservation.

The big question is whether this is just another sharp cyclical correction or the harbinger of something far more serious, a full-blown emerging market crisis? The heterogeneity of the asset class and the way it has developed argues for former. The ability of many governments and corporates in the developing world to issue in their own currency has effectively transferred risk from exchequers and corporate treasurers to investors.

That is painful for investors in the short term, but ultimately positive for debt sustainability. An adjustment via a weaker currency to regain competitiveness is a far better outcome than previous crises when debt denominated in dollars led to devaluation and default. The current sell-off is far from atypical. The time is approaching when a contra-cyclical approach will pay dividends. Waiting for a consensus to build around the merits of emerging market assets is almost always the wrong time to invest.

The flaws of indexation

The highly heterogeneous nature of emerging markets highlights the weakness of traditional benchmark-relative approaches to EMD. Market capitalisation-weighted indices may be appropriate for stock markets because the biggest companies get the largest weighting. Their merits are less obvious in bond markets.

Assigning the biggest weight to the largest issuers of bonds means that investors have the greatest exposure to companies and countries that have the most outstanding debt. That is particularly problematic in emerging markets. Investors are generally less tolerant of high levels of debt and leverage, partly because these economies are generally more susceptible to exogenous shocks, such as the recent collapse in the price of oil.

The US dollar-denominated JP Morgan Broad Diversified index of EM credit is dominated by financials, which make up 33% of the benchmark. Oil and gas issuers account for a further 13% of the index. Managers that are tied to an index to benchmark their performance tend to regard tracking error (deviation from the index weighting) as a proxy for risk. But nothing could be further from the truth in emerging market debt.

The biggest component of risk is often currency: that is why the performance of locally-denominated bonds versus dollar-denominated has diverged so markedly in 2015. The ability to range across the full universe of EMD opportunities – rates and credit – and to short currency exposure, are important risk management tools.

More Related Content...

|

|

|