Private equity co-investments – the need for a careful approach

Written By:

|

Tim Creed |

Private equity has been garnering interest amongst pension funds. Tim Creed of Adveq examines how co-investing can help investors access the asset class

Private equity has been the best performing asset class for many pension funds for a long period of time and data shows it has consistently outperformed public equity over three, five and 10-year periods by around 400 basis points per year.

Co-investing – investing alongside other private equity specialists – has recently gained popularity amongst investors who are looking for a stronger alignment of interests, more control and, ultimately, to amplify the outperformance that is possible through investing in the asset class.

According to Preqin, 10% of pension funds that invest in private equity are already involved in co-investments, forming the second largest co-investor group behind “private equity fund of funds”. However, there are a number of pension funds that are still deciding how to best combine co-investments with their existing investment portfolios.

The appeal of private equity co-investments

A co-investment is typically defined as a minority investment into a target company that is made alongside another private equity investor. In most cases this is a General Partner (GP), i.e. a fund manager that specialises in private equity investments.

Two-thirds of investors that undertake co-investments appear happy with this way of investing and expect their co-investment allocation to increase according to Preqin’s report, “LP Appetite for Private Equity Co-Investments (2012)”. So why have private equity co-investments become so appealing to institutional investors?

An oft-cited reason is that they represent an efficient way of tapping into the attractive returns that private equity provides as this more direct approach offers investors higher returns due to lower and more transparent fees, as co-investments typically have no or limited transaction fees, management fees or carried interest to pay.

Another advantage co-investments offer is the possibility of reducing or even eliminating the so-called J-Curve effect, which is the tendency that private equity funds have to deliver negative returns in early years, followed by investment gains in the subsequent years as the portfolio of companies matures.

Other investors look for co-investments to gain increased control and flexibility over their overall private equity fund exposure. Co-investments can, for example, increase turnaround exposure in order to capitalise on an economic recovery, or increase their allocation to single deals in order to capture opportunities caused by structural changes in a specific sector. Sometimes investors decide to co-invest alongside a GP simply to target the most attractive deals on an opportunistic basis.

Co-investing also allows a valuable analysis into the inner workings of a private equity deal. Some investors decide to co-invest to gain insights into GPs’ abilities and acquire knowledge that will allow them to make better private equity decisions in their fund investments. This is important for institutional investors with a substantial private equity allocation that wish to begin investing solo into deals. Co-investing can be used as a transitional period until enough knowledge has been built internally and the investor is able to establish its own in-house private equity investment team.

The benefit for fund mangers (GPs)

As with any transaction, it is imperative for investors to understand the GP’s motivation behind offering co-investments. It can range from being able to enter into larger deals while retaining control over the investment, to receiving fundraising for their funds more easily, or to benefit from specific expertise that the co-investor may bring to the deal.

Being an active participant in sourcing co-investments from GPs is important, as such investors are often approached by GPs at a much earlier stage than those who have a more passive approach. Having more time to analyse a deal can avert a host of issues that are associated with passive investing. However, it is important to differentiate between sourcing co-investments and sourcing direct deals. GPs often do not like to offer co-investments to investors that have their own dedicated direct investment programme as they see this as a competitor.

Not everything offered is worth taking

Adveq’s analysis of the European buyout market indicates that there is still a large amount of capital to be deployed by large and mid-sized buyout fund managers. Co-investment deals still happen in these segments, but deals tend to become overcrowded. As a result, entry valuations have been rather high and we see what amounts to “mini-auctions”.

The large amount of dry powder available to the industry and the growing appetite for co-investment rights from institutional investors has led to certain GPs offering deals for the wrong reasons. Faced with too much capital to be deployed, they have turned towards deal sizes they do not feel comfortable backing on their own. Some are pressured by their investors to source and offer co-investments as a precondition for future commitments to their regular funds.

Investors able to source co-investment opportunities find themselves in a delicate situation. If they decline too many co-investments, they are at risk of not being approached for future deals, although no one would admit being pressured into participating in a co-investment. By entering co-investments when they are not suitable for a particular reason, there is a real risk of lowering investment standards and of adverse selection, known in the industry as selecting “lemons”, i.e. unattractive deals. To avoid the “lemons” requires getting several aspects of co-investing right.

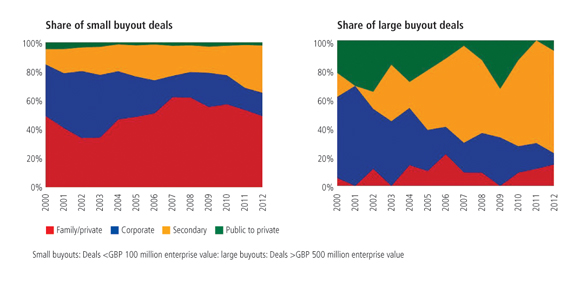

Figure 1. Share of buyout deals

Source: PEInsight, Adveq. 2013

How to access the most attractive deals – leave the herd and look for greener pastures

The first tenet of co-investing is that it should be an extension to existing fund of funds or direct private equity investments. This is important because this decision will drive all subsequent factors, such as deal flow and deal quality. Adveq, for example, targets smaller European buyouts (deals smaller than GBP 100 million) for its primary activity and therefore also for its co-investments.

The small buyout sector is particularly attractive for co-investments for several reasons. First, due to cautious bank lending, equity needs have increased and led to conservative pricing of company interests. This has resulted in a healthy capital supply and demand balance in the market. Second, smaller portfolio companies tend to be transformed more quickly than large companies, and this creates opportunities for private equity investors. Third, smaller companies tend to be family owned, which means the GPs can avoid a full auction process ,and thus face less competition for deals on which price may not be the only criterion. Finally, with over 600 European private equity managers sourcing smaller deals (as opposed to only around 100 European managers in large and mid-sized buyouts combined), there is ample and steady deal flow. For this reason, successful GPs covering the small buyout segment are highly sought after.

It is about who you are and who you know

Fund managers tend to prefer doing co-investments with those investors with whom they have an existing and long-standing business relationship. From a practitioner’s view point, there are several ways to establish one’s standing as a potential co-investor. Adveq, for example has been a first or early investor in 9 out of 10 of their GPs’ funds. In line with the firm’s philosophy of being an active investor, Adveq is also represented in the advisory boards of most GPs and has built a reputation for conducting portfolio-level assessments in its European fund of funds for years. These are all attractive attributes that GPs look for. A GP might have 20-30 investors and yet be able to offer a potential co-investment to only 1-3 investors. Thus, it is vital for the investor to be a highly important, long-standing and value adding investor to the GP.

Selecting deals without cutting corners

Unsurprisingly, GPs will always try to present their deals in the best possible light. In Adveq’s experience it is important to carefully examine the motivation and role of the GP in the deal, as well as to identify the added value a GP can bring to a company after the transaction has been completed.

Regardless of the prior relationship with a GP and the level of conviction of having been offered a deal for the right reasons, accepting a deal requires an independent analysis of the target company also.

Sometimes investors rely on the fund manager’s judgment, or are not willing to invest into the necessary infrastructure to undertake thorough due diligence when they are dealing with smaller companies. However, this is not a recommended approach. Adveq firmly believes that when attempting to pick the best of the best, only a small number of the companies it screens should survive a full investment review.

Executing quickly and consistently

Once the investor has completed its deal-level assessment and given the green light for the deal to go ahead, a number of additional steps still await. In addition to participating in complex negotiations alongside the GP, investors must perform their own due diligence to satisfy various internal requirements. These include, but are not limited to, performing an independent structure review from a legal and tax perspective. Increasingly, investors are also requiring co-investments to comply with their environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards, which introduce another layer of complexity. In light of this, it becomes obvious that investors need to earn a reputation as being highly reliable if they want to be one of those approached first when an attractive opportunity emerges. In fact, GPs prefer investors who swiftly decline a deal over those who drag their feet, or change their mind mid-deal and end up denting both their and their GP’s market reputation.

A closed deal is not a done deal

Once a co-investment has been successfully executed, the monitoring commences. This entails working closely with the GP when approaching the company’s management for updates. It also means actively participating as a member of the advisory board and in the annual valuation process. An expert co-investor will also conduct regular performance monitoring of the GP leading the deal.

Conclusion

Co-investment in private equity deals has become a popular practice for pension funds both large and small, but it is vitally important that it is done right. Pension funds can enjoy many benefits by co-investing in such deals, but being in the right private equity segment at the right time, obtaining access to the best deals, and having a reputation for executing swiftly are all important factors to take into account. Finally, as the fund managers select a limited number of co-investors from a large number of potential co-investors, it is vital for the investor to be a highly-important, long-standing and value adding investor to the GP.

As a result, partnering with a reliable specialist, with a good track record of successful co-investment deals, is vital. Co-investments will continue to be attractive to investors and therefore expert advisers are increasingly focusing on how they can best meet the growing demand. As the allocation to co-investments increases and familiarity with the investment type grows, advisers will be more willing to provide a differentiated set of solutions, which can go as far as assisting investors in building up their in-house co-investments practice.

More Related Content...

|

|

|