Lessons in defaulting politely: controlling excessive debt in developed economies

Written By:

|

Jim Cielinski |

Markets appear to have already forgiven the Eurozone periphery for its past fiscal misdeeds. But what about the US, the UK and, most of all, Japan? These countries possess seemingly intractable debt problems. They are among the world’s largest creditors, seemingly incapable of reining in their free-spending habits, and yet their bond markets remain bastions of stability. Is this behaviour sustainable? Can the debt problems in these countries be resolved? Debt is indeed too high in these economies, but slower growth is the likely outcome rather than a crisis. Many studies have established a link between high debt loads and growth. For countries with debt-to-GDP ratios of more than 100%, for example, the growth potential has been projected to be lower by 0.75% to 1.25% pa. annum. Repayment ability is seldom impaired however, particularly if the debt is denominated in local currency. The US, the UK and Japan all have many tools at their disposal to address the debt issue; they have only just begun to use them.

Japan has long been the poster-child of debt largesse. With a debt-to-GDP ratio of more than 200% and a looming demographic time bomb, it is often singled out as a crisis in-the-making. In reality, this merely reflects a lack of understanding of how crises play out. Japan, in fact, has been enduring its own form of debt crisis for over two decades. A crisis need not be defined by fireworks and panic – it can also be a long, drawn-out period of sub-optimal growth and asset depreciation. This is the lesson of debt overload.

Defaulting politely

Failure to repay – or debt restructuring – is the most dramatic form of debt crisis. This outcome is simply not a realistic option for most Western economies. Outside of policy ineptitude, there is no incentive to pursue this most fatal of options. In Japan, for example, more than 85% of government bonds are held domestically. The Bank of Japan can print money indefinitely, buying Japanese government bonds with the proceeds. This will preclude default, but the side-effects may be much higher inflation or a dramatically weaker currency.

Excessive debt must ultimately be liquidated in some manner. Actual default is only one of the many options for doing so, however, and will be reserved primarily for economies with high levels of debt denominated in an external currency. Other options are summarised in Figure 1. Although less dire than default, the effects of some of these options are often similar.

Figure 1: Excessive debt – what is the cure?

Source: Threadneedle, April 2014

With so many sensible options for liquidating debt, and with default risk off the table, it becomes clear that intractable debt loads should most often lead to lower yields, not higher.

Debt reduces both growth and price pressures and, as witnessed in Japan, can perversely produce the world’s lowest bond yields in the world’s most debt-laden economy. This is also why peripheral Eurozone bonds have rallied so strongly. As the ECB dialled down default risk, excessively high real rates collapsed under the weight of dismal growth and low inflation.

Different countries will pursue different options. For most, a range of strategies will be used. A common theory suggests hyper-accommodative monetary policy will be used to “inflate the debt away”. But this is unlikely, and is only possible if policymakers continually surprise the markets. If markets suspect such a ruse, rates should immediately reflect an abnormally high risk premium, pushing borrowing costs to levels that induce a deflationary slowdown. The UK is perhaps the only country that might be able to pursue this option, given the very long average maturity of outstanding debt. Given the exorbitant costs, we do not believe this will happen.

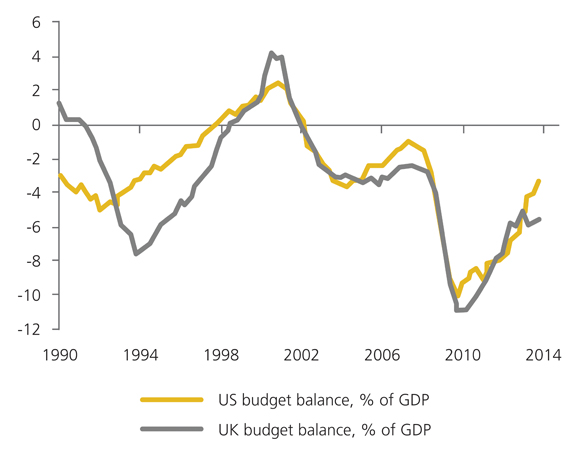

Figure 2: US and UK budget balances as a percentage of GDP

Source: Bloomberg, April 2014

Can the debt problem be fixed?

The endgame is still a very long way off. Yes, many economies are over-levered, but debt burdens are well under control given the low levels of interest rates. We expect rates to move higher in the coming year due to cyclical reasons, but the structural drivers of low rates will persist. The fundamentals behind debt sustainability are already improving markedly.

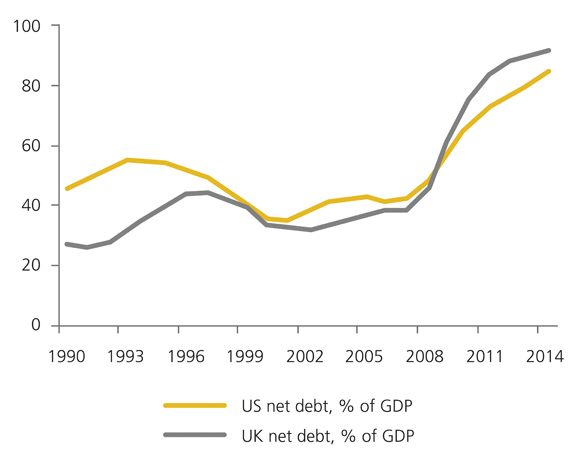

Debt sustainability will remain elusive. Debt-to-GDP ratios will worsen in coming years, even in an economic recovery. At current rate levels, for example, 4.5% nominal growth in the US is necessary simply to maintain the status quo. Markets should not grow dejected. This already represents a stunning improvement from just 18 months ago, when debt-to-GDP ratios were on a trajectory to exceed 100%. Figures in the 70-80% range now appear feasible. Moreover, there is greater clarity around available options. In the US, health care costs are the perennial “budget killers”, currently projected to rise at 5.8% per annum. Merely reducing health care inflation to 2-3%, however, will be sufficient to reduce debt ratios to 40% of GDP within the next 15 years. Options are also plentiful in the UK. If policymakers are able to hold borrowing costs 1.5% lower than inflation over the next 4-6 years, as they have recently been able to do, debt sustainability will be within their grasp. Japan has a tougher task, requiring GDP growth and structural reform.

Figure 3: US and UK net debt as a percentage of GDP

Source: Bloomberg, April 2014

Time will tell if these options are viable. No one should doubt the resolve of policymakers, however, and no one should underestimate the degree of flexibility still available to them. If these options fail, there is always the option of doubling down. Japan is exercising this option today.

A sovereign borrower should never be confused with a corporate borrower. Countries play by different rules. If a country has its own central bank, its own currency, the ability to tax, and the debt is mostly held and/or denominated in local currency, the flexibility to avoid a credit crisis is far better than perceived. Governments cannot fully rewrite economic rules, however, and the heavy debt loads will restrain growth for many years to come.

What does this mean for interest rates? The severe rate increases of 2013, in our view, reflected the unwinding of extreme QE-induced market distortions. The next phase, which we expect to kick off in the second half of 2014, should see rates rise on the back of a cyclically-improved outlook. Rates are unlikely to soar, however, and a debt crisis remains a very distant threat. The debt hangover is more likely to lead to sluggish growth, low inflation and a continuation of accommodative policy.

Important information: For use by investment professionals only (not to be passed on to any third party). Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of investments and any income is not guaranteed and can go down as well as up and may be affected by exchange rate fluctuations. This means that an investor may not get back the amount invested. The research and analysis included in this document has been produced by Threadneedle Investments for its own investment management activities, may have been acted upon prior to publication and is made available here incidentally. Any opinions expressed are made as at the date of publication but are subject to change without notice. Information obtained from external sources is believed to be reliable but its accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. The mention of any specific shares or bonds should not be taken as a recommendation to deal. Issued by Threadneedle Asset Management Limited (“TAML”). Registered in England and Wales, No. 573204. Registered Office: 60 St Mary Axe, London EC3A 8JQ. Authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority.

More Related Content...

|

|

|