Is the time right for European equities?

Written By:

|

Niall Gallagher |

Many investors consider European equities “uninvestable”. They see a number of convincing reasons for avoiding the asset class ranging from the woes in Greece, Spain, Ireland and other peripheral European nations, to concerns over a lack of political cohesiveness at the centre of Europe, and fears of undercapitalisation in the banking sector.

We reject this simple consensus and think there is much to appreciate about investing in Europe. The continent has some excellent companies with world-leading products and services, and global reach. Europe’s economies are not uniformly poor, and the asset class is undeniably cheap.

We believe that an active investment approach is the only way to exploit Europe’s diverging economic trends and avoid the potential pitfalls. Indeed, the current negative sentiment towards European equities has created some very interesting investment opportunities.

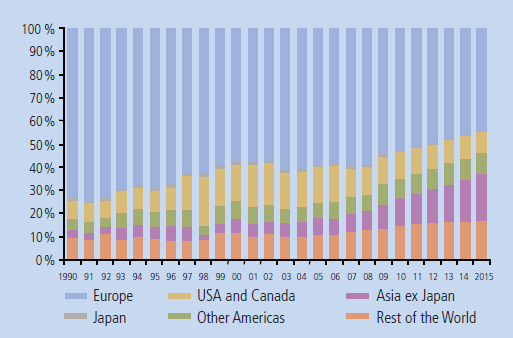

Global Europe. The geographic revenue composition of Europe’s listed companies is illustrated in Figure 1. It shows that corporate revenue streams coming from outside of Europe have grown steadily over the past 20 years, and that the consensus is that they will continue to grow in the coming three years. As a result, European equities have become an increasingly poor proxy for Europe’s economies.

This globalisation of revenue streams has been driven by the emerging markets. This trend should not surprise anyone familiar with European companies, many of which are now truly global. For instance, the brewer AB InBev derives the vast majority of its revenues from North and South America. Swatch sells nearly a half of its watches to Chinese customers. Industrial services companies such as SGS and Kuehne + Nagel benefit directly from the needs of a globalising economy. Meanwhile, the lift companies Kone and Schindler are focused on China and other emerging markets, where long-term urbanisation trends are supportive of continued investment in residential property. It is therefore unwise to equate the troubles in European economies with its corporate sector.

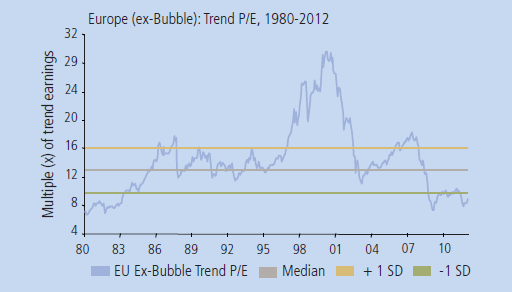

Cheap Europe. We find European equities very attractively valued. Based on price-totrend earnings, they trade at a significant discount to the 30-year median valuation. This is illustrated in Figure 2.

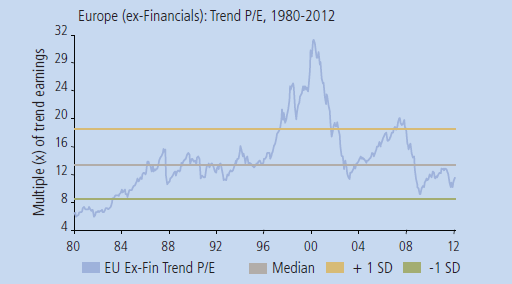

Some argue that Europe appears cheap because of the undercapitalisation of its banking sector. Although we agree that some European banks need recapitalisation, the market is also cheap relative to history when excluding banks (Figure 3).

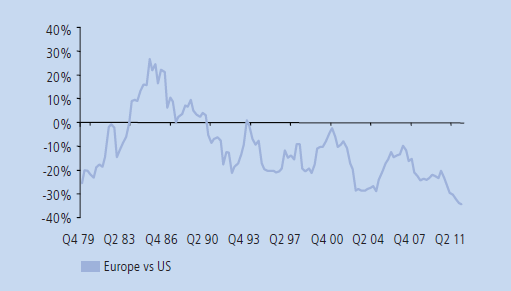

Valuations are also compelling relative to other asset classes. Comparing Europe’s price-to-trend earnings valuations with those of the US over a 30-year period (Figure 4), we find that Europe currently trades at a record-high discount of 37% to the US. This is despite European companies’ more global reach, the fact that both markets have enjoyed similar trend earnings growth rates of some 7% over the past 30 years, and despite Europe’s average discount of just 10%. It seems to reflect deep scepticism towards the asset class rather than considering the fundamentals.

It may be useful to remind ourselves what has happened to the European market since 2000, as this may partly explain the excessive pessimism displayed towards the asset class. As can be seen from Figure 2, the European equity market has seen a painful valuation compression from nearly 30x trend earnings to the current 8x. So while aggregate corporate earnings have continued to grow, the market has experienced an extensive de-rating. The MSCI Europe index has lost over 40% of its value since its peak in 2000 and this derating, together with high equity market volatility, has had a major impact on sentiment. It leaves the asset class undeniably cheap.

A tale of two Europes. It is clear, however, that a number of European countries will need to make significant adjustments to their economies in order to deal with the painful aftermath of real estate bubbles, uncompetitive domestic economies and over-grown state sectors. The private sector’s inability to fund state largesse has become central to the bond markets’ mindset in several countries.

The need for fiscal austerity and public sector retrenchment has received much commentary already. Our view is that the most important issue to solve concerns the deflation of asset bubbles and the consequent deleveraging within the private sector. Such deleveraging is likely to be extensive and drawn-out, with significant implications for banks and domestically-exposed companies in many countries.

In Spain and Ireland, the need for private sector deleveraging creates headwinds for growth, which should be considered when selecting stocks.

However, the focus on peripheral Europe has led many to overlook the strength of Germany and other northern and central European economies. This strength derives from a combination of strong external sectors, exports to faster growing parts of the world, high employment levels and better contained fiscal accounts. These economies also tend to benefit from a tradition of saving, and thus a less excessive build-up of private sector debt.

We do not believe that the northern and central European economies are immune from global conditions but their prospects do vary greatly from those of peripheral Europe. Their need for economic adjustment is much less severe. Hence the headwinds for domestic demand are weaker.

In some respects, we see similar trends at a global level. While global growth remains reasonably healthy overall – and in line with the longterm average growth rates – there are significant divergences between countries and these have important investment implications.

Europe: investment strategy. The divergence in European fundamentals highlights the merits of an active investment approach. There are some truly great businesses in Europe trading on attractive valuations, but also areas that will be impacted by private-sector deleveraging and the general turmoil affecting Europe’s periphery. In addition, there are sectors that are not as defensive as they used to be, and others that face specific challenges. That is, all is not good in Europe.

It seems to us that the excessive pessimism expressed towards Europe is based on the very real troubles of peripheral Europe, but it masks the attractiveness of some world-leading companies with great growth prospects and high returns on capital employed. A passive investment strategy is incapable of avoiding such pitfalls and could lead to poor performance. In contrast, a genuinely active investment approach is wellplaced to take advantage of such opportunities.

More Related Content...

|

|

|