Investo-Masochism: How a passive approach to investing can lead to suffering

Written By:

|

Carl Moss |

|

David Schofield |

Carl Moss and David Schofield of Intech explore some misconceptions about passive investing

There are few fields of endeavour in which we start with the intention of being average. Body weight, maybe, or golf but certainly not exam grades, incomes or pensions. In fact, we generally strive to outdo others in most areas, or at least do better than average.

Yet in investments the prevailing wisdom appears to be that mediocrity is acceptable, maybe even aspirational. Many in the institutional investment community consciously decide they are satisfied with one particular, very specific way of measuring the market’s average return, and pay fees to managers to replicate it. These “index managers” are amongst the largest investors in the industry, stewards of trillions of dollars. Mass reproduction, you might call it.

Of course, much of the recent interest in index management can be attributed to the global financial crisis. This was traumatic for investors and profoundly challenged many of the assumptions which were confidently held. We now look forward with less certainty than we did before the storm. In this environment it is only natural that investors would want to look for safety in their equity portfolios. But the fear of careering off track has led many investors to want to sit squarely in the middle of the road – and we all know what eventually happens to those who do that.

One argument for this questionable behaviour is that active management – or deviation from the index in an attempt to generate a superior return – does not work for everyone: it is often stated that the average “active” manager underperforms the benchmark, after fees. And over some periods this statement is true: but it is, however, a red herring.

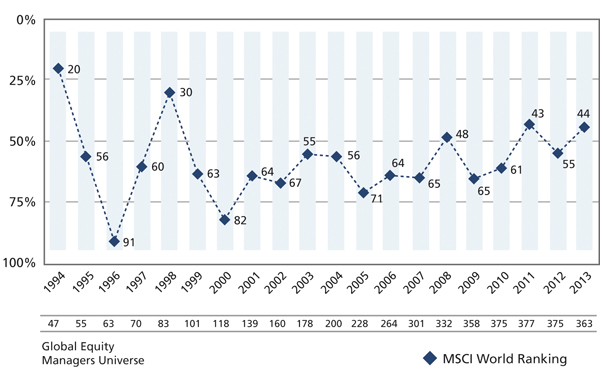

Figure 1 shows how the MSCI World Index would rank if it were compared to a broad set of global equity managers.

Figure 1: How the market ranks against managers

Source: eVestment Alliance Database: Global Large Cap Equity

Over these 20 years the market – and therefore any indexer – would have mostly delivered below-average performance.

At any one time there are plenty of managers who outperform, and plenty who underperform. But in aggregate they (by definition) match the market returns, and therefore apparently underperform after allowing for fees. Yet there is no more an “average” active manager than there is an “average” family with 1.7 children and 0.4 dogs.

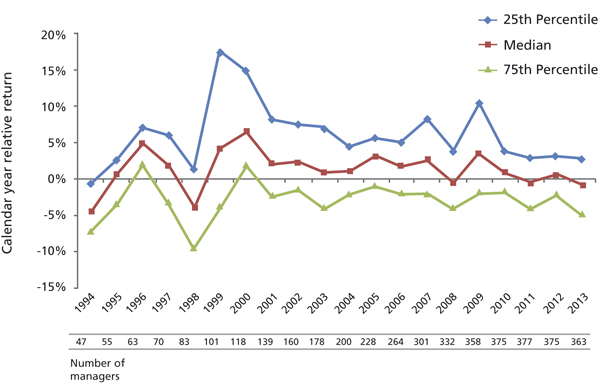

The key is, of course, to select the better managers: those who have an above-average chance of outperforming and do so, most of the time. An entire industry exists, employing many intelligent, experienced people, with the goal of attempting to identify such managers. Many of them succeed. Figure 2 shows how well a good manager can do: here we show the top quartile, median and bottom quartile amongst global equity managers against the MSCI World Index. In every year except one, a top quartile manager added more than value than would have been taken by the average amount of fees.

Figure 2: A good manager adds significant value

Source: eVestment Alliance Database: Global Large Cap Equity

Another misleading argument for indexation is that alpha is a zero-sum game. For every bit of alpha generated by one investor, so the story goes, another investor, somewhere, somehow has lost the same. The conclusion drawn is that investors therefore shouldn’t bother trying to generate alpha. It is true that not everyone can beat the market: as we have seen, the market return is the average of all investors’ returns. Alpha is just the amount by which an investor’s return deviates from the average, and everyone understands we can’t all be above average. But it doesn’t mean investors should stop trying.

It also certainly does not mean that Peter must be robbed to pay Paul. But this is often thought to be the case. It appears to some that, if hedge funds hadn’t done so well, scores of poor pensioners would all be better off, and going on endless cruises instead of turning the heating down a notch.

This is akin to arguing that your high exam score actually causes someone else to do worse, or that his above-average shoe size causes someone else’s feet to be smaller. The market doesn’t have a fixed total value to share around between investors. It is of course self-evident that for everyone who has an above-average return, someone must be below average; but that doesn’t really tell us anything useful. And it certainly does not mean markets are zero-sum games in some absolute sense. Stock markets can and do grow. Total wealth can increase for everybody but not at the same rate for all, depending on how you invest your money. Finding those managers who are able to generate consistently above-average returns, though not easy, is a worthwhile exercise.

And we shouldn’t forget how worthwhile it can be. Although some point out that passive investing is very cheap, sometimes even free, to lock in those mediocre index returns, they rarely point out the opportunity costs of foregoing the alpha generated by an outperforming manager. Let’s be optimistic and say that the stock market will have compound returns of 8% a year for the next 30 years. The pension fund that invests £100 million today in an index fund will end up with about £1 billion with which to pay its pensioners in 2045. But a pension fund able to identify a manager with true skill, who is able to deliver just an extra 1% net per year – a fairly modest target – would end up with £1.3 billion. This is £300 million more than the index-fund investor has accumulated, with which to pay out benefits. An extra 2% net would give the fund an extra £700 million to distribute. By comparison, that decision to invest passively is suddenly looking like the more-expensive option.

Here is the power of compounding returns consistently over long periods, an important element in this discussion. Finding a manager who can achieve modest but consistent outperformance over time – with robust risk management – is arguably more important than finding an aggressive manager who will give you the occasional year of stellar returns but with a great deal of volatility. Most of his good years are spent, if you’re lucky, just about making up for the bad. Volatility of returns is the enemy of compounding, and there is a mathematical relationship between the two that quantifies how volatility erodes growth of capital. Other things being equal, the tortoise beats the hare in the long run.

The last refuge of the passive apologists is of course “efficiency”: big companies are widely followed by hordes of analysts. Their information is freely available and reflected in stock prices; because of this, it’s not possible to get an information advantage over others, so stock picking is a mug’s game. We should all just follow the herd and buy index funds because such markets are “efficient.” This is like arguing that since one brick is like any other, all houses must be equally well-built. Such reasoning entirely overlooks the fact that it is possible to beat the market by means other than trying to guess which stocks will do well, such as by more intelligent portfolio construction and better risk management.

The typical index portfolio buys into each company in proportion to its size. The bigger the company, the more you invest until you end up with a reasonably diversified portfolio of hundreds of stocks, spreading the risks around somewhat. But little thought has gone into precisely how many eggs you have in which particular basket. It’s been 60 years since Harry Markowitz’s pioneering and Nobel-prize winning work showed that the aggregate riskiness of your stock portfolio depends, among other things, on how the stocks in the portfolio move around relative to one another. In other words, the correlations between stocks are important if you want to manage the risk of your portfolio. If all the stocks tend to jump around in unison (high correlations), your portfolio will also tend to be pretty volatile, like the stocks it contains; however, if the stocks’ movements tend to offset one another (low correlations), the portfolio’s overall riskiness tends to be less than that of the stocks in it. It turns out that, if you exploit this effect simply by re-jigging the stocks in the index to take into account these correlations, you can actually make a portfolio that has the same, or even less risk than the market, but a higher expected return. In other words, you have a more efficiently constructed portfolio comprised of those already efficiently priced stocks, and an above-market return, even in the most efficient markets, without picking stocks.

Even taking all this into account, passive investing has actually gained in popularity recently, supported by half-understood and misapplied theory. Substantial amounts of money with which to pay pensions benefits are being left on the table by fiduciaries content to endure the market returns without attempting to improve upon them. Perhaps it is not for nothing that the very word “passive” has at its root the Latin word for “suffering.”

Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. There is no assurance that the investment process will consistently lead to successful investing.

More Related Content...

|

|

|