Illiquid credit investing demystified

Written By:

|

William Nicoll |

As businesses continue to experience difficulties in securing bank lending, William Nicoll of M&G discusses the investment opportunities for pension funds

If one of the problems you face is not having enough ready cash with which to pay pensions, then illiquid credit might provide an answer. Investments in illiquid credit derive almost all of their returns from current coupons rather than projected market increases. This may appeal to anyone who wishes to move away from selling investments and realising returns to raise cash to pay pensions.

A long history

When ancient Sumerian farmers needed tools, they leased them from local officials. And when the officials dutifully noted down who had borrowed what and when, they unwittingly created the first recorded lease agreements.

Now, 4,000 years later, pension funds are doing something similar. They are providing money for the sort of lending that enables businesses, housing associations and economic projects to function more effectively – and at the same time offer attractive levels of risk, return and security.

This is illiquid credit. It is based on the age-old principles of lending money, bringing clear benefits to borrower and lender, and it is no wonder the UK pension funds are showing ever greater interest.

Three pillars of illiquidity

Illiquid credit investments tend to fall into three camps. Some are long dated and pay a fixed or inflation-linked income, others have a medium-term life and offer floating rate returns that are linked to interest rates, while still others pay unusually high returns to compensate for their complexity and small pool of available buyers.

Just about everything that a pension fund could invest in today, tomorrow or in five years’ time was once seen as a natural loan for a bank to make. This explains why the investments are illiquid. There was a time when there was little need to materially alter the agreement between the lending bank and the borrower during the life of a loan. Neither was there an opportunity for any other party to become involved.

Now, pressured by regulatory and commercial considerations, banks are finding loans such as these too expensive or too unattractive to renew, and are pulling back from vast chunks of the market. They have also effectively stopped packaging loans or assets up for investors (as they cannot make money from trading them).

Their loss is a pension fund’s gain. Investing in these assets can provide an institutional investor with an income stream in excess of that from corporate bonds, from risks not available in public bond markets. This is a market where investors want to be paid more to hold things that can be difficult to understand and hard to sell.

The illiquidity premium

While this market can offer investors a premium over liquid opportunities with similar levels of credit risk, what it does not offer is a fixed illiquidity premium.

In fact there is no such thing as a set illiquidity premium. Any return premium in this market is subject to change and some transactions can be so sought after that their illiquidity “premium” is actually negative.

This happens because the best investment opportunities attract growing interest from prospective buyers. An increase in demand causes a loan or asset’s pricing advantage to start ebbing away. First movers get the best assets for the best prices.

For nimble investors, with the discipline and patience to secure attractive prices, additional returns from illiquid credit are generated by three factors – sometimes individually, sometimes in combination.

Illiquidity compensates an investor for a lack of a secondary market for the asset, meaning it would most likely be held until maturity. Here, an asset class would be mature, with a number of investors willing and able to hold the assets. Leveraged loans and private placements are good examples.

Second is complexity, where an asset has a structure that makes it off-putting or time-consuming to analyse and understand for all but the most adventurous or well-resourced investors. Many long-lease property transactions fall into this camp.

And lastly, there is a premium for the hard work of creating investment opportunities. Commercial mortgage loans and social housing debt fall into this camp. In these cases, an owner of a hard asset wishing to raise debt finance but unsure of the best structure to do so approaches an asset manager to structure the transaction.

The process of sourcing illiquid credit assets can be a resource-intensive, intricate and convoluted process. This hard work deters some investors, leading to low demand. Those with the appetite and skills for illiquid credit can exploit these factors and achieve higher returns than from comparable, more popular liquid assets.

How to invest

The usual access points apply in illiquid credit – via an investment manager or investment directly. Whichever route a pension fund chooses, they must consider pricing and structure before investing.

Here, there is no publicly published pricing, no consistent supply and no secondary market. There are also some investors with a strong motivation to buy almost regardless of price. There has also been downward pressure on spreads (the difference between the yield of a risky security and “risk-free” government bond) across the entire credit market post crisis. However, the spreads of different illiquid assets have contracted at different rates. This makes some highly attractive at present, while others may become so in future.

All of these factors make pricing both difficult and important. That is because the cash flows that a loan or asset will deliver over the source of its life are, in most cases, the primary source of value to investors: a price is derived from the sum of all future cash flows. Get the right price and a pension fund can feel more comfortable.

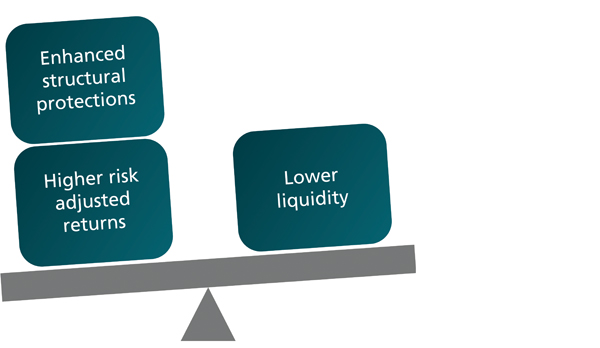

Figure 1: The illiquid credit trade off

Source: M&G, October 2014

Illiquid credit investing is a simple trade-off: what is lost in liquidity is gained in higher risk-adjusted returns and structural protections that can be superior to those offered by public bonds. That means the second thing for pension funds to consider is security. Generally speaking a lender will attain a first or near first ranking in the capital structure. Sometimes they will also have a substantial claim on the borrower’s buildings or other assets.

While there are no uniform agreements, a typical illiquid structure will see covenants that offer protection to an investor in the event the asset does not perform as expected.

For example, in a direct lending investment, covenants typically require the borrower to maintain debt ratios within set limits, and will hold talks with the lender should the business come close to breaching any of them. In these cases, the lender can be compensated by the company for amending or waiving the covenants giving additional returns to the investor.

Moreover, the bilateral nature of illiquid credit investment means that lenders can talk to borrowers about any problems in the agreement at an early stage. This early warning system can not only head off problems and limit downsides but can also increase a lender’s recovery levels.

Pension funds should therefore consider that illiquid credit can offer the sort of reliable, predictable and fairly secure income streams that could address some of the challenges they face. This is something very akin to the risks and returns from the sort of assets in a fixed income asset allocation bucket, although of course the nature of illiquid credit offers true diversification from the limited number of names available in the public corporate bond market.

To do well here, an investor must understand these assets and all of the factors that influence their pricing, to know what to buy and when to buy it. To that end, success will likely come to those willing to work hard and then wait until pricing is at its most favourable.

For Investment Professionals only.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. This article has been distributed for educational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed. Opinions are subject to change without prior notice.Statements concerning financial market trends are based on current market conditions, which will fluctuate. There is no guarantee that these investment strategies will work under all market conditions.

The services and products provided by M&G Investment Management Limited are available only to investors who come within the category of the Professional Client as defined in the Financial Conduct Authority’s Handbook. They are not available to individual investors, who should not rely on this communication. M&G Investments is a business name of M&G Investment Management Limited and is used by other companies within the Prudential Group. M&G Investment Management Limited is registered in England and Wales under number 936683 with its registered office at Laurence Pountney Hill, London EC4R 0HH. M&G Investment Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

More Related Content...

|

|

|