How real estate investing can have a real social impact

Written By:

|

Nick Montgomery |

|

Paul Myles |

Nick Montgomery and Paul Myles of Schroders examine the economics of place-based investment, showing how this not only helps to minimise regional inequalities but can also provide a better financial outcome

Real estate investment is uniquely placed to address the UK’s major social inequality, and institutional investors can work in partnership with local government and other stakeholders to deliver place-based impact investment.

Academic studies suggest that the UK has one of the highest levels of regional inequality among developed economies and it is sometimes argued that the UK would achieve faster growth if economic activity were spread more evenly through a “Northern Powerhouse” or “Midlands Engine”. It has also been suggested that the 2016 Brexit vote was, in part, a protest by people in slower growth areas who perceive their living standards to have stagnated and has resulted in the government’s “levelling up” agenda.

Data shows that unemployment and low wages are highly correlated with poorer health, higher crime rates and inadequate housing, resulting in areas of multiple deprivation, and Covid has disproportionately-affected people in deprived areas. Many institutional investors are now keen to participate in a place-based solution. Given the positive impact these investments can have on both the social as well as economic outlook of an area, we strongly believe both demands can be fulfilled to the benefit of all stakeholders.

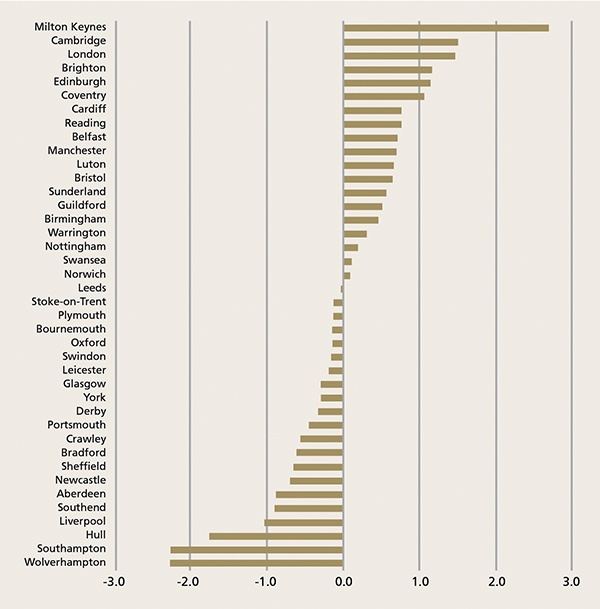

Figure 1: Variation in economic growth across 40 UK towns and cities between 2010 and 2020

Source: Oxford Economics, Schroders. December 2020. 603806.

Figure 1 shows the variation in economic growth across 40 towns and cities between 2010 and 2020. On average the UK economy grew by 0.4% pa. however, eight cities grew by more than double the national average and five places experienced virtually no growth, even before Covid.

Big cities have generally seen faster economic growth than towns and smaller cities in the same region. In the north-west, Manchester has grown faster than Liverpool and Warrington; Bristol vs Swindon, Leeds vs Hull.

One explanation for the success of Cambridge, Coventry and London is that they have attracted dynamic companies across sectors. The fact that big cities have generally seen faster economic growth is consistent with the theory that businesses in the same industry benefit from clusters, or agglomeration. They may see faster growth, but what was the catalyst which started the virtuous circle? How can a struggling town turn itself around and create a strong local economy?

A diversified economy, with a variety of different industries and differently-sized companies, generally means that a town or city will be more resilient in a downturn. Start-ups are important for innovation and job generation. Cities dominated by one or two large companies run the risk of atrophying in the long term.

A related factor is a highly-educated labour force: the long-term growth in professional and technical jobs – the “knowledge economy” – has raised demand for graduates. There is a broad correlation between the ranking of the 40 locations in Figure 1 and the percentage of the population with a degree.

IT, advanced manufacturing and life sciences firms are increasingly locating facilities close to leading universities and research institutes because new products are becoming too complex to develop in-house. Universities are responding to commercial collaboration and supporting academics to launch start-ups to boost royalties from intellectual property.

New projects that support good physical infrastructure such as Crossrail, HS2 or the planned Transpennine rail upgrade influence where companies decide to locate and where people choose to live. However, free-flowing traffic within urban areas is also important, achieved by improving bus services and encouraging more people to cycle or walk.

Climate change means that other types of infrastructure including flood defences, the electricity grid and water supplies are becoming increasingly important. For example, the risk of a water shortage is highest in London and the south east, but it could also be a problem in Birmingham, Nottingham, and even Manchester despite its reputation for rainfall! Fixing leaking pipes will help, but it will not solve the problem. Other measures will be necessary, including building more reservoirs, creating a national network to pump water from regions with plentiful water supplies, and harvesting rainwater for flushing toilets.

A fourth important factor for a successful local economy is strong leadership and public-private cooperation. Those who use local services are better placed than Whitehall civil servants to make decisions on them. But leadership is not just about local government, it must also connect councillors, non-profit organisations and business, academics and financiers.

Finally, it clearly helps if a city is an attractive place to live with a mix of old and new buildings, a range of cultural attractions as well as living opportunities. Milton Keynes and Reading lack the charm of Brighton or Cambridge but they have a wide array of leisure facilities. It is critical that these individual factors are combined in a wider regeneration plan, as no single factor is a guarantee of economic and social success.

Inequality also varies within cities. Although data shows that Hull, Liverpool and Middlesbrough had the highest number of deprived neighbourhoods relative to their size in 2019, deprived areas are not confined to slower-growing local economies. London and Manchester have a large number of deprived areas and Brighton, Coventry and Milton Keynes also have pockets of extreme deprivation. It is an inconvenient truth that some of the UK’s fastest-growing cities are also among the most unequal.

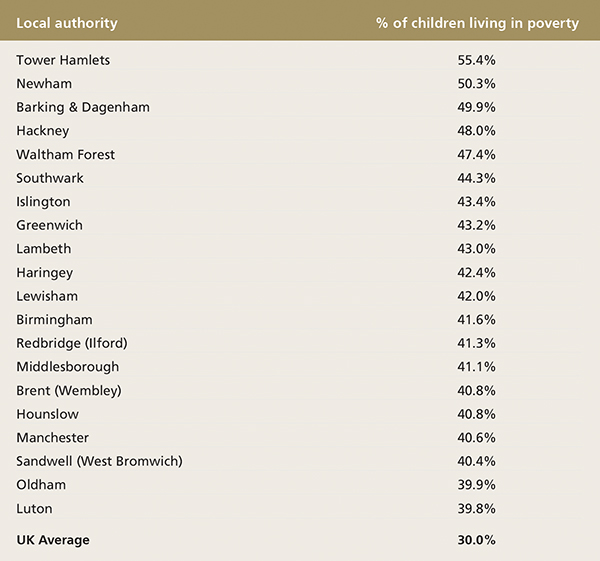

Social housing shortages mean that many people on low incomes have no choice but to live in private rented accommodation. While housing benefit or universal credit meets some of the extra cost, these are capped. The squeeze on disposable incomes is greater in faster-growing cities, where there is strong competition for rented accommodation. Figure 2 lists the 20 local authorities with the highest rates of child poverty, defined as the percentage of children living in families with a disposable income – after housing costs – of less than 60% of the national median. As might be expected, some of the highest rates are in places with relatively weak economies.

Figure 2: The 20 Local authorities with highest child poverty rates in 2018/19

Source: Local indicators of child poverty after housing costs. Donald Hirsch, Juliet Stone, Centre for Policy Research, Loughborough University and the End Child Poverty Coalition, 2020. 603806.

The shortage of housing in London means that 40-50% of children in inner London live in poverty, despite many of their parents working. The data above is for 2018/19 and, unfortunately, there is a significant risk that child poverty has increased during the pandemic because it has disproportionately affected families on lower incomes, especially those on flexible or zero hour contracts. Can UK cities continue to function and prosper if people on lower incomes can no longer afford to live there due to acute housing shortages?

Traditionally, property investors have focused on assets in affluent locations. Demand is typically strong which provides liquidity. However, while most investors will continue to concentrate on maximising financial returns, Schroders believes there has been a fundamental shift towards strategies which generate positive impact.

The perceived conflict between fiduciary duty and sustainable investment reflects a historic view that social benefits and investment returns are drawn from the same, finite pot. The value of companies or assets is increasingly tied to the social benefit they provide. Pension funds and asset managers’ fiduciary duties increasingly require incorporated sustainability and positive social impact into investment strategies as a result.

More importantly, we believe that investment with social and environmentally-sustainable impact will actually drive additional positive economic outcomes and thus enhance financial returns over the long run. A combination of social awareness and wider fiduciary responsibilities towards a broader set of stakeholders, as well as further governmental regulations will steer the investment market. Real estate with positive social and environmental features is less likely to suffer from obsolescence and is more likely to retain its value over time.

We believe a clear priority should be given to building new housing, particularly affordable and social housing for people on low incomes. The government’s decision to abolish the housing revenue borrowing cap in 2018 has removed one of the main obstacles to local authorities building more homes.

Another major challenge facing deprived areas is town centre regeneration. Not only do people in deprived areas have less money to spend, but house prices and commercial values are often too low to make void spaces viable for development for alternative uses. The government wants to help regenerate town centres but it will not succeed without private investment.

An increase in jobs through the provision of office, retail and industrial space at a discounted rent to start-up businesses, charities and non-profit groups would provide a new form of local income. Investors should also consider different economic models that would allow schemes to incorporate new public spaces. The key starting point for all these initiatives is to take a “hospitality mindset”: what services do the local stakeholders require and how could these services be delivered?

We believe that place-based impact investment does not mean a lower financial return and in fact, could drive more sustainable financial outcomes in the longer run. Increased public/private collaboration is required to tackle the problems of UK inequality. Given the positive impact that place-based investment can have on local communities and economies, we strongly believe that both impact and financial interests can be fulfilled to the benefit of all stakeholders and it is possible to construct a diversified UK real estate portfolio which will deliver a positive real return, in a financial sense, and in tangible impact solutions.

More Related Content...

|

|

|