Foundations of the future

Written By:

|

John Malloy |

John Malloy of RWC Partners looks at the opportunities for investing in infrastructure projects around the world, taking GDP per capita as one criterion for investment

The election of US President Trump has focused much attention on his plan for significant infrastructure investments in the US. We believe infrastructure investments can act as catalysts to longer-term productivity enhancements and stronger economic growth, and see many examples of this dynamic across both emerging and frontier markets.

Significant progress in access to basic infrastructure has been made over the past 25 years. However, over 1.3 billion people worldwide still have no access to electricity. That is nearly 25% of the population in developing nations and seven out of ten people in sub-Saharan Africa (Washington Post, 2012). Also, 660 million people still live without safe drinking water and 2.4 billion are without access to basic sanitation (WHO/UNICEF joint monitoring programme 2015 report). This shows that there is still a significant need to improve even the most basic of infrastructures.

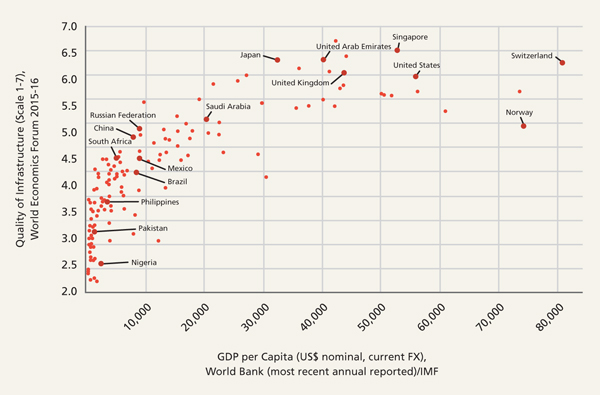

GDP per capita is a good indicator of the quality of the infrastructure in a country, and Figure 1 shows a strong connection between the two. In essence, EM and FM are in the sweet spot for infrastructure-driven growth opportunities.

Figure 1: Infrastructure quality vs GDP per Capita

Source: World Bank, IMF

As GDP per capita increases in emerging markets, so does spending on infrastructure, and this directly impacts the quality infrastructure in place. As GDP per capita increases, governments are required to spend more on infrastructure, and people demand higher quality of transportation.

To attract the investment needed to drive economic growth, governments strive to outdo each other in demonstrating their efficiency in delivering goods and services to companies and individuals. As an example, each day in transit is estimated to cost between 0.6% and 2.0% of the value of traded goods (OECD 2015, Hummels and Schaur, 2012). By way of another illustration, the lack of a reliable electricity grid in Nigeria is estimated to add approximately 40% to the cost of goods and services due to the use of private generators, and this is thought to represent a drag on annual GDP growth of between 3-4% (OECD 2015, OBG, 2012). Higher efficiencies require better and more modern infrastructure, which in turn have a positive impact on growth.

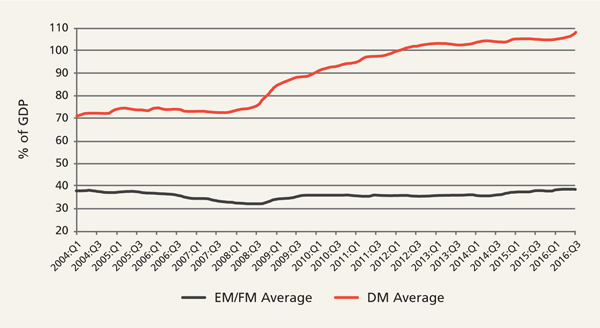

Spending on real public investment as a percentage of GDP has been going down over time, but it remains higher in emerging economies than in developed countries. Growing urbanisation and increasing population in emerging nations force governments to upgrade the quality of the infrastructure. Emerging economies have a lower debt-to-GDP ratio than developed countries, and the gap has increased since the financial crisis of 2008. This will enable many EM/FM economies to undertake additional infrastructure spending.

Figure 2: Government debt-to-GDP ratio

Source: RWC Partners, Haver Analytics, 01 January 2004 – 30 September 2016

After an extended period of very low interest rates coupled with quantitative easing, the world is still showing relatively anemic growth. This then raises the question of what additional measures can be taken to improve growth prospects and job creation going forward. Improvements in infrastructure are not only necessary to accommodate future economic and social development, but could boost future growth when monetary easing stops and fiscal expansion takes over. This would kill two birds with one stone: higher growth and better living conditions.

The OECD estimates in a 2015 report titled Fostering Investment in Infrastructure that the total global infrastructure investment required between 2007 and 2030 will come to a staggering $72 trillion. That is approximately 3.5% of the GDP over that same period. Governments, however, have a finite financial pool with which to improve infrastructure. As a consequence, we are seeing a global trend of more private sector capital and expertise entering the financing, building and operating of infrastructure projects. These projects are called Public Private Partnerships (PPP) and can take various forms of ownership. PPP ventures have expanded the listed infrastructure sector substantially and have created a deeper pool of potential investments for investors like us.

The following are some examples of major infrastructure hot spots in emerging and frontier markets.

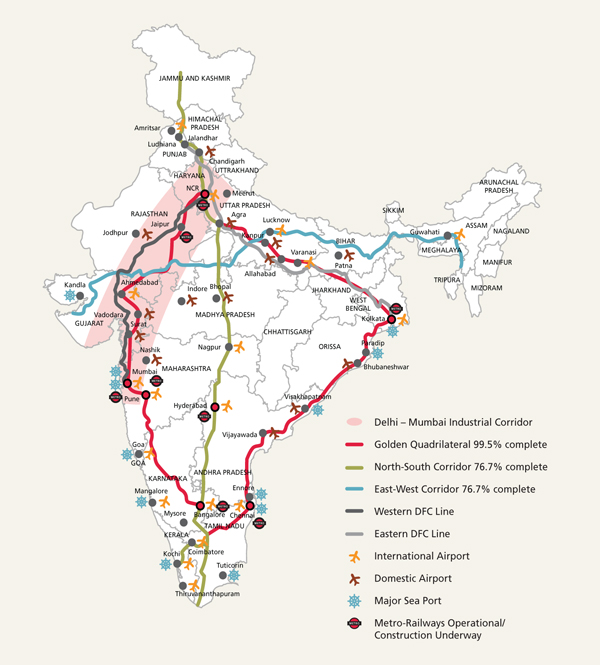

India

Finance minister Arun Jaitley said in June 2016: “India needs over US$1.5 trillion of investment over the next 10 years to bridge the infrastructure gap as the government intends to connect 700,000 villages with roads by 2019 as part of a massive modernisation plan. In terms of highway construction this year alone our target is 10,000 kilometers. Our railway system is over 100 years old. We are going in for massive modernisation.” According to Macquarie Infrastructure, a population of 1.25 billion – two thirds of whom are under 35, GDP growth rebounding to a forecast 7.5%, headline inflation numbers which have lowered to their sub-5% target and consequent low interest costs, means that India’s macro-economic environment is one of the best in the world.

Figure 3: The infrastructure landscape of India

Source: Jones Lang LaSalle Research

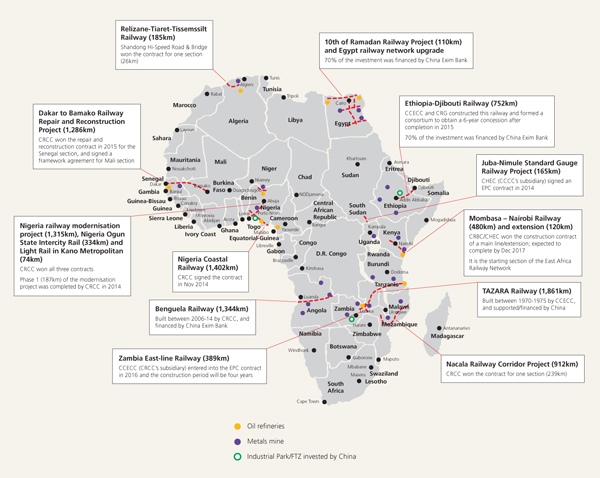

Africa

We see various economic benefits from African railway projects, highlighted in Figure 4.

Figure 4: China’s railway footprint in Africa

Source: Company data, Bloomberg, Xinhua News, People.cn, China Railway Construction News, Gaotie.cn, UBS

- A new profit driver for Chinese construction companies and equipment makers.

- Easier access to the rich natural resources in Africa.

- An increase in economic co-operation, through the development of China-established Industrial Parks and the Africa Free Trade Zone.

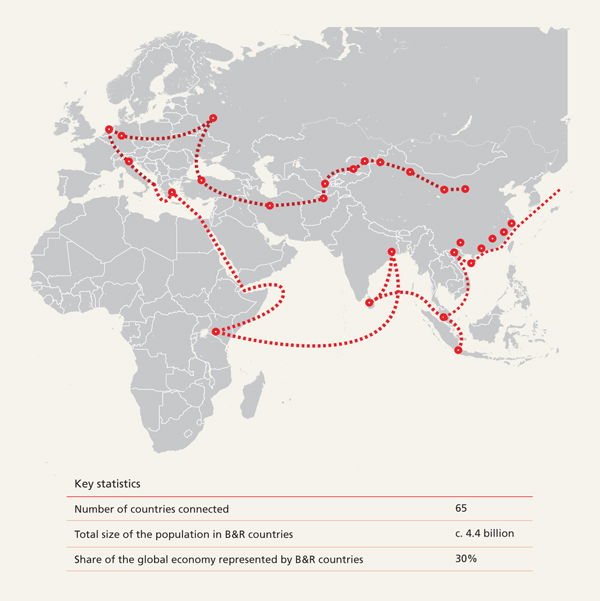

One Belt, One Road (the new “Silk Road”)

One Belt, One Road is a planned network of road, rail, marine routes, pipelines and other infrastructure designed to connect China with Central Asia, South and Southeast Asia, Russia, Europe and Africa. The project is underpinned by a drive for greater trade and financial integration, as well as improved communication and information links. The estimated investment is $900 billion.

Figure 5: Belt and Road – China’s new Silk Road

Source: PwC

As emerging markets continue on the development path, we believe investors will benefit from tapping into the infrastructure required to facilitate growth opportunities. Infrastructure is a theme that has appealed in emerging and frontier markets, and which is strongly represented in our portfolios.

More Related Content...

|

|

|