Fossil fuel divestment – a solutions-based approach

Written By:

|

Martin Grosskopf |

Addressing climate change concerns purely through fossil fuel divestment can not only impact negatively on investment returns, but could also restrict the ability of investors to have a positive impact on environmental issues. Martin Grosskopf of AGF Investments examines the options

Recently, major asset owners have made headlines with their decisions to divest fossil fuel assets from their portfolios. As discussion surrounding climate change grows, institutional investors are increasingly incorporating environmental and social risks into their financial assessments, and decisions to move away from fossil fuel companies have been increasing.

Recent major announcements of divestment have included:

- Norway’s enormous US$850 billion sovereign wealth fund has divested from 114 companies over the past three years – mostly coal-mining companies but also oil sands and other fossil fuel companies. The fund cited the outsized risks of high carbon emissions, deforestation and poor water management as reasons for divestment.

- Stanford University’s US$19 billion endowment fund announced a divestment from 100 coal companies in May 2014, becoming the largest endowment to divest from any part of the fossil fuel industry.

- In September 2014, the Rockefellers Brothers Fund, a US$860 million philanthropic organisation run by the heirs to the fortune built by John D. Rockefeller, announced that they would exit all fossil fuel investments in their portfolios.

- In the UK, the London Assembly voted in March 2015 to divest the fossil fuel portfolio of the £4.8 billion managed by the London Pension Fund Authority.

It has become increasingly evident that what initially began as a grassroots campaign on university campuses to encourage university endowment funds to divest of fossil fuel investments has grown substantially in a short period of time. A 2013 report from the University of Oxford¹ concluded that the fossil fuel divestment campaign was growing quicker than any earlier divestment movement. Recent data has shown that in just nine months, from January 2014 to September 2014, the number of commitments by universities, churches, cities, states, pension funds, and other institutions more than doubled from 74 to 181. In summary, more than US$50 billion has been divested from fossil fuels so far.²

And momentum is continuing – much of it driven by the younger millennial generation, whom studies have shown are twice as likely than the broader population to invest in companies or funds that target specific social or environmental outcomes.³ Student movements across the world calling for fossil fuel divestment have led to over 500 active divestment campaigns underway at universities, cities, churches, banks, pension funds, and other institutions.

Governments, academics, institutional investors and other stakeholders have taken notice. Recently, a bill has been introduced in California by the state Senate leader requiring California’s two state funds – CalPERS, the public employees’ pension fund, and CalSTRS, the teachers’ pension funds, to divest of all coal holdings. And in Canada, university professors at the University of Toronto, the University of British Columbia, University of Victoria, Simon Fraser University and Mount Allison University have mobilised to urge university directors to divest their school’s endowment funds from fossil fuels.

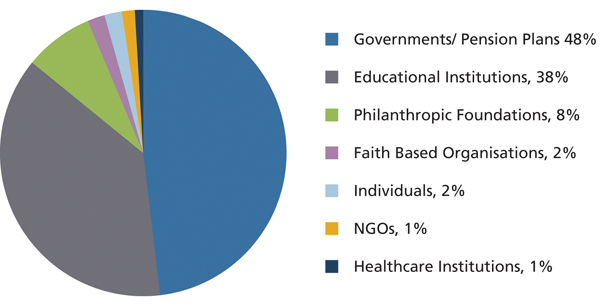

Figure 1: Divestment by stakeholder ($50 billion)

Source: Arabella Advisors, September 2014

Why are they divesting?

At the Copenhagen Accord in 2009, governments from around the world (including the governments of Canada, the United States, China, Brazil, the United Kingdom, and the 27 European Union members) agreed that actions should be taken to keep any global temperature increase to below 2˚C above pre-industrial levels. If temperatures rise anywhere above this level, climate change risks become unacceptably high. Rising temperatures have dire consequences for food and water security, global infrastructure and the health of humans and ecosystems. They can also increase the frequency and intensity of extreme weather anomalies and the risk of geopolitical conflict. Cities that could find themselves under threat from rising water levels include New York, Boston, Los Angeles, Vancouver, Shanghai and many others.

A recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) suggests that global temperatures have already risen 0.85°C since 1880⁴ and that up to another 0.2°C may be in store as past emissions take a decade or more to fully affect global warming. Thus, scientists estimate that globally, we are already due for approximately 1° of warming.

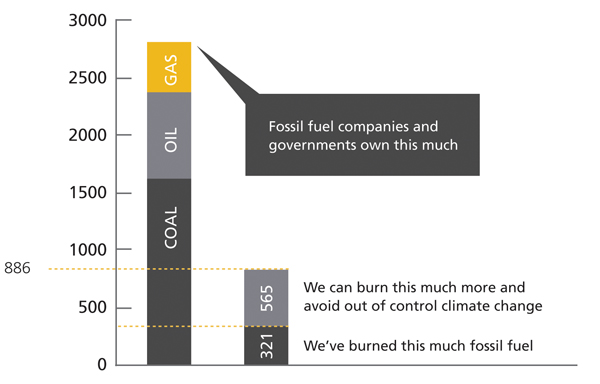

Recent research has suggested that the world can only afford to produce 565 more gigatons of carbon dioxide to maintain an 80% chance of meeting its target of keeping global warming below 2°C. However, current global proven fossil fuel reserves amount to a massive 2,795 gigatons, which implies that approximately 80% of current reserves must remain underground.⁵ With many international government subsidy regimes favouring the continued expansion of fossil fuel extraction, a new approach is warranted if the world is to prevent further global warming. Hence, the fossil fuel divestment campaign was born as investors began to mobilise in an effort to address the problem.

Is there a divestment penalty?

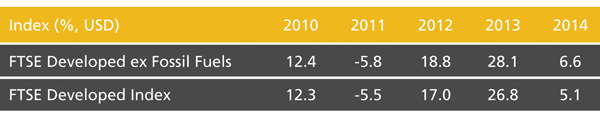

One of the most common caveats to divestment campaigns is that excluding fossil fuel stocks from portfolios may lead to underperformance. More recently, in response to the growing interest in fossil fuel divestment campaigns, some index providers have been introducing fossil fuel-free indexes to track performance. In October 2014, MSCI announced the launch of the MSCI Global Fossil Fuels Free Exclusion Indexes, citing a “response to clear demand from asset owners.” FTSE, meanwhile, has been tracking a fossil-fuel free index version of its FTSE Developed Index since 2010.

As a result, it is relatively simple now to track the performance of a fossil fuel-free portfolio versus the broader market. A look at the returns of the FTSE Developed ex Fossil Fuels Index reveals that it has outperformed its fossil fuel-inclusive peer in four out of five calendar years since inception.

Indeed, divestment of fossil fuels may actually prove to be financially beneficial over time. Where the debate comes full circle is around the issue of “stranded assets” – the idea that as the world approaches its burnable carbon limit and governments adjust policy accordingly, the remaining fossil fuel assets suffer from unanticipated or premature write-offs, downward revaluations or are converted to liabilities. One could argue that these risks are poorly understood and regularly mispriced, leading to over-exposure in environmentally unsustainable assets in the financial system. And as the climate change debate grows in importance over time, the risk for “stranded assets” in unburnable fossil fuel reserves escalates.

Figure 2: Global fossil fuel reserves vs acceptable carbon levels

Source: Carbontracker.org as of December 2014

Redefining fossil fuel-free – a solutions-based approach

In our view, the growth of the fossil fuel divestment campaign has been an encouraging development. However, divestment alone is not a solution to the problem. Given the enormous size of the asset class, divestment has a long way to go before it can make an impact.

Although the divestment campaign has been remarkably successful in a short period of time, it remains unlikely that most investors will completely divest from fossil fuel exposure. When oil, gas and coal prices are strong the resulting cash flows are simply too attractive to ignore for most investors who are focused on meeting short-term investment objectives. With a market capitalisation of US$4.5 trillion⁶, the fossil fuel industry is unlikely to be capital constrained outside of periodic price collapses.

While most investment industry professionals make the argument that engaging with companies to improve their environmental impact is a more prudent approach, we believe engagement – while helpful – is not enough either. This is largely due to the inclusion of fossil fuel and energy companies in several investment benchmarks, such as those produced by MSCI or S&P, and their prominence in measuring investment performance. Straying too far from these benchmarks ensures greater volatility, which in turn increases the risk measures of the investment strategy. For this reason, even most “responsible” investment portfolios will have close to market weight exposure in fossil fuel companies. In our view, the need to align investment strategies with conventional benchmarks limits the extent to which the industry can contribute to tackling complex issues such as climate change.

Whether or not an investor is invested in a particular industry or Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS) sector may be a relevant risk management question for portfolio construction, but not necessarily from an environmental standpoint. For instance, approaches rarely consider the interplay with other environmental objectives such as sulphur emissions or water use, and do not measure the benefit or cost of a company’s product.

Paradoxically, it is possible to reduce portfolio carbon risk while still owning large emitters of carbon if they are relatively efficient. Similarly, optimising for one factor such as carbon may eliminate companies that make significant contributions to other environmental objectives such as water quality or clean air.

In other words, we would argue that the divestment movement has often assumed that removing an industry or GICS allocation altogether is the most meaningful approach to tackling climate change. Our view is that owning solutions is a better approach. We are relatively unconcerned on where a company falls within a particular GICS sector and more concerned about whether they have a product or service that is leading to an environmental benefit. We employ an impact investing approach – looking for companies that can generate a positive environmental or social impact, along with a financial return on investment.

Figure 3: Calendar year performance – total return

Source: FTSE, as of December 31, 2014

Focusing on the long term

We have found that when companies are aligned according to their ability to contribute to – and benefit from – key sustainability themes, the resulting map provides a different context in which to make investment decisions. The investment process becomes future focused and long-term in nature, unlike investing based on benchmarks, which provide a snapshot of today’s economy. An investment strategy based on this approach is holistic in the sense that multiple environmental objectives are tracked and the interactions made explicit. The investment team can then focus on allocating capital to – and engaging with – companies that are offering sustainability solutions.

The AGF sustainable investing team has optimised thematic analysis over 20 years to create portfolios with positive impact. AGF Global Sustainable Growth Equity Strategy offers a solutions-based approach focusing on the upside of environmentally-friendly products and services while giving investors the opportunity to participate in innovations that are disrupting incumbent industries and offering environmental benefit.

While the carbon intensity of these portfolios are materially lower than conventional benchmarks, this is not accomplished, as is common practice, through ownership of sectors with low carbon intensity such as Financials and Telecommunication Services. Companies in these sectors generally have yet to demonstrate that they are sufficiently focused on sustainability solutions to merit inclusion. Instead the portfolio is sector agnostic but thematically diversified – an appropriate emphasis for environmental solutions.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the Portfolio Manager as of May 2015 and should not be considered investment advice or a solicitation to buy or sell securities.

AGF Investments is a group of wholly owned subsidiaries of AGF Management Limited, a Canadian reporting issuer. The subsidiaries that form AGF Investments manage a variety of mandates comprised of equity, fixed income and balanced assets. AGF International Advisors Company Ltd. is authorised by the Central Bank of Ireland and regulated by FCA for conduct of business rules in the U.K.

1. “Stranded assets and the fossil fuel divestment campaign: what does divestment mean for the valuation of fossil fuel assets?”, Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford, 2013

2. “Measuring the Global Divestment Movement”, Arabella Advisors, September 2014

3. “Sustainable Signals: The Individual Investor Perspective”, Morgan Stanley Institute for Sustainable Investing, February 2015

4. IPCC 5th Assessment Report

5. “Unburnable Carbon – Are the World’s Financial Markets Carrying a Carbon Bubble?”, Carbontracker.org

6. Bloomberg New Energy Finance, August 2014

More Related Content...

|

|

|