Exploring fossil fuel divestment

Written By:

|

James Mowat |

James Mowat of Majedie Asset Management considers the question of investing in the oil & gas sector in light of challenges posed by climate change

Asset owners and asset managers face a major challenge. How should they try to influence the capital allocation of their investee companies to improve ESG engagement, particularly in relation to climate change, and for all to earn societal trust? Climate change is a crucial component of the environmental factors considered in company research. This includes an assessment of the potential risks it may pose under a variety of scenarios and, equally importantly, the business opportunities it may provide.

Clearly it is more pressing for some sectors than others; none more so in most investors’ minds than for the oil and gas sector. It is therefore important to consider the merits of whether or not to invest in the sector in light of the challenges posed by climate change and the opportunities that could come from a transition to low-carbon energy source.

Divestment is one option available to investors, but it means that the shares may be bought by investors who do not care about long-term environmental issues. Any resulting fall in oil company share prices would mean their cost of capital rises, reducing their ability to invest in clean energy. Falling oil and gas production would lead to higher energy prices and we do not think this aligns with the objective of eradicating poverty consistent with the 2015 Paris Agreement. At worst, it may draw coal and other more carbon-intensive energy sources back into the mix.

In addition, state-controlled oil and gas companies, which are more opaque and relatively less accountable, would take a greater share of global oil and gas production if quoted companies sold their assets. Investors can have an influence over private sector capital allocation decisions, but have none over national oil companies.

Engagement with companies is therefore an important tool which can help achieve a more responsible approach to the environment. Investors should consider and debate strategies and the quality of information flows each time they meet a company’s management or assess a company’s results. Investors have the opportunity to push for reform, as required, and should only hold shares where they are confident that companies are operating in a sustainable and profitable fashion.

Our experience with Ophir Energy, an oil and gas company, is an example of this approach. We sold our stake in the company after extensive engagement with the board when we found the management was not able to deliver on our original expectations of good project governance on a key oil field. Exploration and production companies often operate in unstable jurisdictions and it is critical they do so to the highest standards. Delivering on that basis can take more time than standard project finance may allow, which was a factor in our decision to divest.

By contrast, the largest oil and gas companies can operate to the highest standards, even in challenging political environments. Put simply, they have the resources to take the time that is needed to complete a project according to the standards their investors and local jurisdictions require. Companies such as these can be held to account on their governance at individual project as well as at board level. It’s a good idea to assume that they will not get everything right and factor that into the valuation.

Climate change background

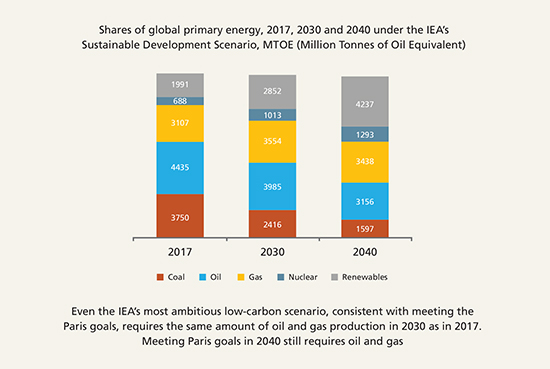

The Paris Agreement from 2015 set the goals of keeping a global temperature rise this century below two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius. When we think about climate change, we consider what needs to happen for the world to meet the Paris goals, referred to by the International Energy Agency (IEA) as the Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS). Total world energy consumption under the Paris agreement needs to remain flat until 2040, despite a growing world population and increasing economic activity. This situation is evolving fast, as the latest report by UK’s Committee on Climate Change recommends the government introduce legislation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050. A great deal of work needs to be done to reduce energy consumption per person through greater efficiency as well as the carbon intensity of that energy. The bar chart in Figure 1 shows how long it will take to move the dial and how key oil, and especially gas, are to driving down coal consumption. This analysis underlies climate change protesters’ sense of urgency. They feel that the energy transition is too slow. However, gas generates half the carbon of coal so provides a bridge to a less carbon intensive future, while alternative technologies scale up.

Figure 1: Energy sources – now and in the future

Source: OECD/IEA 2017 World Energy Outlook, IEA Publishing

Big Oil: more sinned against than sinning?

Despite issues relating to climate change, we own BP and Royal Dutch Shell in our client portfolios, taking the view that these companies will provide solutions to climate change over time while representing attractive investments and serving current energy needs. We understand the controversy which surrounds them, but believe it needs to be kept in proportion for several reasons:

- The threat of action by stock market investors can influence management action, as policy changes at BP and Shell have shown. Both companies now include their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the metrics for executive pay as a result of combined shareholder pressure. We believe this process can and must continue, through on-going governance.

- It is government policy which is central to meeting Paris targets, not the actions of a few large oil companies. Worryingly, given the paucity of public sector initiatives, it is highly unlikely that global energy consumption will achieve the target levels consistent with the Paris Accord by 2040. The worst fears of the Royal Society and Bank of England Governor Mark Carney could well be realised. The private sector can always act – and we believe companies such as BP and Shell are improving on this front – but governments need to lead.

- BP and Shell do not produce coal, and the gas they produce has about half the carbon intensity of coal. In addition, the fossil fuels they produce will be required in a lower-carbon energy mix – especially gas – as developing economies need energy for more of their populations to rise out of poverty.

- International oil companies can only invest significant sums in renewables as public support and government policy permits. Companies need greater magnitude licencing to deploy at scale – national government policy is generally weak and intragovernmental cooperation is at a low point. As climate change campaigns gather momentum and voters become better informed, we think societal pressure will build and BP and Shell will be ready and able to scale up their renewable operations.

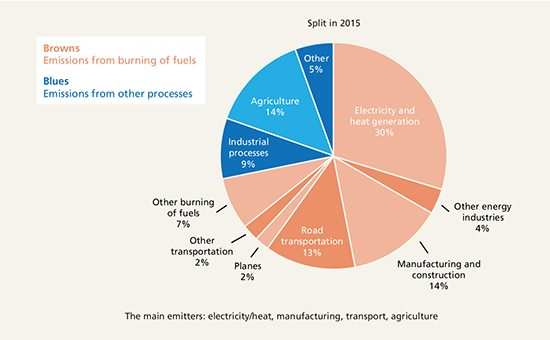

- The world’s seven largest oil companies, known as Big Oil, and the burning of their products, only make up 10% of global CO2 emissions. Within that 10%, only one tenth comes from emissions generated by the oil companies and the energy they use themselves (and is part of the “other energy industries” slice of the pie chart in Figure 2). The rest is produced when customers (we) burn those fuels to power factories, homes, planes, trains, cars and so on, as the chart below shows.

Figure 2: Global CO2 emissions in 2015, split by sector

Source: IEA

Conclusion

The energy transition is now within the timescales of pension funds and millennials starting their first savings. The race for energy efficiency is intensifying. Countries and companies alike are committed to meeting the climate change goals and pledging to become more sustainable. What once seemed like an outlying interest area for public sector funds, charities and environmentally aware savers, is now mainstream – a structural shift for asset owners and asset managers alike. As an investor, you should ensure that your fund managers apply their investment expertise, experience and shared philosophy to use their influence with investee companies to improve their ESG signature wherever possible. It is important to keep sight of the fact that, ultimately, we are all stakeholders.

More Related Content...

|

|

|