Environmental, social, governance (ESG) and the spectrum of capital

Written By:

|

Karen Shackleton |

Karen Shackleton, Senior Adviser at MJ Hudson Allenbridge, considers the different investment approaches that are open to pension fund managers when considering their commitments to ESG investment

With ESG becoming increasingly mainstream, pension fund investors are being bombarded with a plethora of new investment approaches ranging from ESG investing to sustainable investing, from ethical investing to impact investing, from green investing to social investing. In its paper to the World Economic Forum in 2019, UBS noted that there were over 80 terms used to describe the range of strategies and approaches that have evolved in this space. No wonder there is confusion over the different terminology!

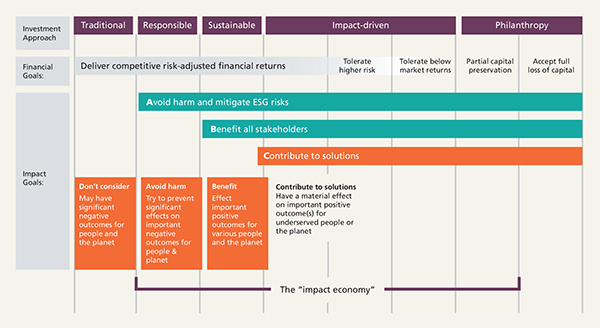

One of the more helpful schematics is the “Spectrum of Capital” (Figure 1). Rather than focusing on definition of terms, this schematic focuses on the financial and impact goals of the investor.

Figure 1: The Spectrum of Capital

Source: The Rise of Impact: Five Steps Towards an Inclusive and Sustainable Economy, UK National Advisory Board on Impact Investing, 2017 & Impact Management Project, 2017

On the right-hand side of the schematic is “philanthropy”. This is obviously unsuitable for a pension fund where fiduciary duties must prevail. On the very left-hand side is “traditional investing”. Here the investor is focused only on financial goals, the aim being to deliver the most competitive risk-adjusted financial returns, even if such investments have a negative outcome for society or the environment. This was a common style of investing in the 1980s when pension funds began to adopt a “balanced fund management” approach, investing in a diversified mix of asset classes with the goal of achieving the maximum risk-adjusted return.

In the past decade however, environmental, social and governance concerns have become increasingly important. Institutional investors have shifted towards the next column on the spectrum of capital, becoming responsible investors. Here, the investor continues to focus on risk-adjusted financial returns, but ESG risks are now considered, insofar as these might impact the future return to the investor, either positively or negatively. These days, it is extremely rare for a fund manager not to mention ESG when describing their investment process. Even private markets managers are taking ESG risks into account prior to making investments.

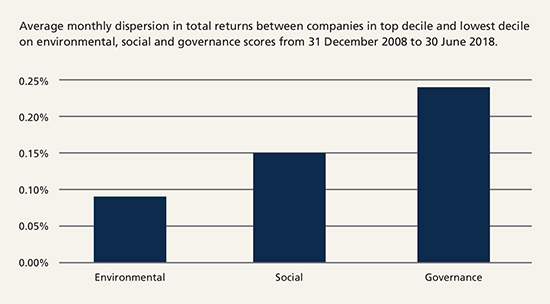

A recent survey by Hermes suggests that this is a very sensible thing to do (Figure 2). They analysed the average monthly dispersion of returns between listed companies when ranked by ESG scores, for the 10 years to 2018. Small but noticeable benefits accrued when investing in companies with top decile rankings, compared with bottom decile companies, particularly with respect to governance scores. In other words, companies that have superior ESG scores performed better, over time (not that this should come as a surprise).

Figure 2: ESG value is driven by corporate governance and social characteristics

Source: Hermes Investment Management as at 30 June 2018

Investors can access these benefits in several ways. First, the asset manager must take ESG considerations into account in their buy/sell decisions. Second, the investor can vote to support or oppose the board’s recommendations at AGMs which can improve governance. Many funds have voting policies around director remuneration, for example. Third, the investor can actively engage with the management of the companies in which they invest. Collaborative bodies such as LAPFF have been effective in this respect.

Some pension fund investors are beginning to move further along the spectrum of capital, towards “sustainable” and “impact-driven” investment approaches. In the first two approaches, traditional and responsible, no moral views on the ESG risks are taken – the investment decision is purely around the potential financial impact that ESG risks can have. With sustainable approaches, the investor’s values are now brought into the discussion. This might involve thematic decisions. For example moving a passive investment strategy to a low-carbon index fund in order to reduce the carbon emissions, or the carbon footprint, in the pension fund’s portfolio. Yet it is still possible to achieve these goals without financial detriment to the members of the pension scheme.

The more interesting space, in terms of recent innovation and development, is in impact-driven approaches. The spectrum of capital classifies this approach into three separate sub-categories:

- Investments where there is no detriment, in terms of the financial return;

- Investments where there is no detriment to the financial return but where the investor is happy to tolerate a higher risk (for example, less liquidity);

- Investments where some loss in return is tolerated.

As far as the investment’s impact goals are concerned, these investments are more intentional in nature, so contribute to social or environmental solutions in an additive way. In other words, society or the environment is better off than it would have been without the impact investment.

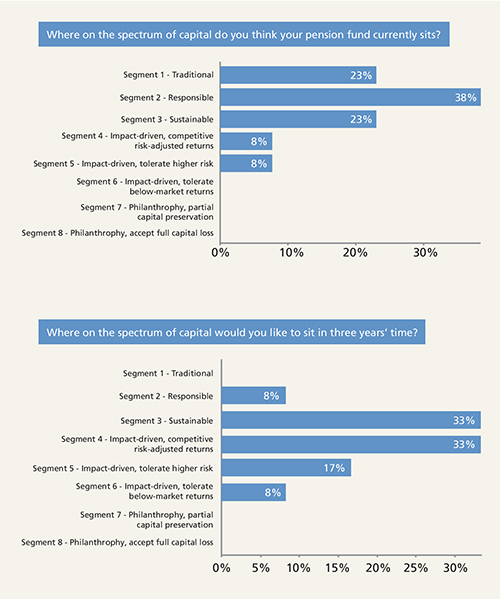

There is no doubt that impact investment is likely to grow in popularity amongst pension funds over the next three years. At the DG Publishing/Pensions for Purpose Investing with Impact Summit in 2018, pension fund delegates (a mix of corporate and LGPS funds and their independent investment advisers) were asked where they sat on the spectrum of capital today, and where they would like their pension fund to be in three years’ time (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Investor trends

Source: DG Publishing

The results are insightful, with a very definite shift towards the right of the spectrum of capital. Fifty-eight per cent of respondents wanted to be investing with impact in three years’ time. It is little wonder that the asset manager community is responding positively to this growing interest.

One of the major concerns of the investor sits around the financial performance of impact investments. Most of the 58% who wanted their pension fund to be impact focused expected their investments to deliver market-rate returns. Indeed, this is the simplest way to ensure that fiduciary responsibilities are being met (although below-market return investments can still contribute positively at the total fund level if they have a low correlation with the other investments in the portfolio). Yet much of the scepticism around impact investment revolves around their financial performance.

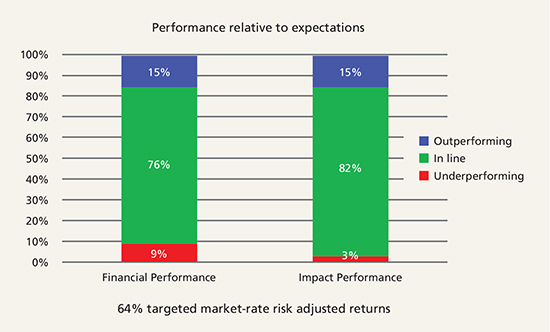

The Global Impact Investor Network (GIIN) has produced insightful research on this subject, in their annual survey of investors (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The financials of impact investments

Source: GIIN 2018 Investor Survey

In 2018, 91% of investors felt that their impact investments had performed in line with expectations, or better, in terms of financial performance. Nearly two-thirds of these were market-rate investments. In listed markets, these might be investments in pharmaceutical companies developing drugs to help fight cancer, or investments in bonds that are funding environmental projects (so-called green bonds). In unlisted markets, it might be a property fund investing in residential units to house the homeless, or an infrastructure fund investing in renewable energy, or micro finance to developing countries. GIIN’s latest analysis shows that the impact market is an estimated $502 billion globally. This has most certainly become an investment approach that is here to stay.

What is most important is that those responsible for the pension fund take time to discuss and articulate their investor beliefs and to then agree where on the spectrum of capital they would like their pension fund to be, given their fiduciary duties. That discussion will, in turn, determine the investment approach that can and should be taken, resulting in a clear narrative for the fund’s investment strategy statement.

More Related Content...

|

|

|