Emerging markets: a good time to invest or better to wait longer?

Written By:

|

Christian Kopf |

Christian Kopf of Union Investment takes a detailed look at the outlook for investment in emerging markets, including a consideration of specific countries and an assessment of the major asset classes

Market environment

Bonds, currencies and equities from the emerging markets (EMs) faced challenging market conditions in 2018. Besides idiosyncratic country-specific factors, the main problems were not only rising yields in the US on the back of the Federal Reserve’s series of interest-rate hikes but also the appreciating US dollar, the trade dispute instigated by Donald Trump and the threatened – and in some cases imposed – sanctions on individual countries and companies. Crude oil prices rose for long periods. This, combined with the weak local currencies of the emerging markets, meant that importing oil became significantly more expensive for many countries while commodity-producing countries suffered as a result of decreasing prices for industrial and precious metals. This caused bond spreads to widen and share prices to fall, in some cases by a long way.

Many of the negative factors have now been priced in. Leaving the financial crisis to one side, valuations have now reached a level that would have constituted a buying opportunity in recent years. We cannot yet say without qualification that it is definitely time to invest in the emerging markets. However, there certainly are opportunities for long-term investors who are aware of the associated risks. Another important point is that sentiment in the capital markets has recently brightened somewhat. This trend may indeed continue in the coming weeks and months, depending on a number of influences. Investors therefore need to be ready to take action and make decisions.

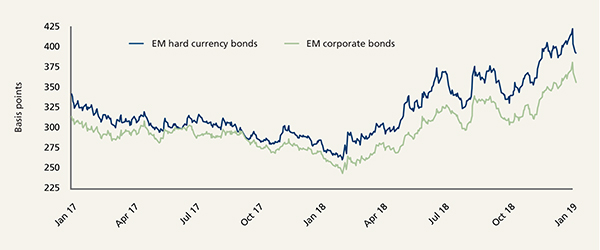

Figure 1: Continual widening of spreads since February

Source: Bloomberg, Union Investment, as at 8 January 2019

Trade dispute remains a risk factor, despite easing recently

The trade dispute between China and the US will play a big part in determining what happens going forward. At the start of last year, the markets were in agreement that the dispute would not escalate. But as the months passed, the spiral of tit-for-tat restrictions continued. The world economy has now reached the point at which the punitive tariffs are starting to have a clear impact, including in the form of faltering global trade and cost-push inflation that is eating into profit margins in affected companies and sectors. Uncertainty about what might lie ahead is unsettling companies and the markets, and they are acting very cautiously.

At its annual conference on 12-14th October 2018, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) lowered its global growth forecast from 3.9% to 3.7% for both 2018 and 2019. In the IMF’s view, the uncertainties created by the trade disputes will increasingly act as a brake on growth. At the same time, there is an ever-stronger feeling that, underlying the simmering trade disputes, a broad paradigm shift has taken place within US foreign policy, and the US is on a path of strategic confrontation with China. The real issue is China’s burgeoning influence in Asia and the fact that Chinese companies, such as Tencent and Huawei, are increasingly becoming the new technology leaders. Moreover, Beijing wants to extend the “New Silk Road”, whereas the Americans are positioning themselves as the better trading and geostrategic partner for many Asian countries. Washington has identified trade as China’s weak point and is using this to push through its demands and pursue tangible economic and geostrategic interests.

This makes it very difficult to foresee how the Chinese-US relationship will pan out, and there is a constant switch between small signs of détente and verbal confrontation (as seen recently at the APEC summit). At the G20 summit, which took place in Argentina on 30 November 2018, the decision-makers from both sides came face to face again. In our view, the talks represented an easing of the situation, but the dispute was certainly not resolved. This was made clear almost immediately, when the CFO of Huawei was arrested in Canada on suspicion of violating US sanctions. Given these mixed and volatile signals, we have to wait and see what will happen in the bilateral trade relations between the world’s two biggest economies in the weeks and months ahead.

Global monetary policy becoming gradually more restrictive

Another key influence on the emerging markets is the normalisation of monetary policy in industrialised countries. The US Federal Reserve is continuing along its path of interest-rate rises for the time being, but will align its monetary policy a lot more closely with the economic data than it did in 2018. However, the Fed is likely to raise interest rates at a slightly slower rate than previously expected and now anticipates just two hikes in 2019, rather than three (median prediction). This suggests that US yields will continue their gradual ascent, at least at the short end of the US Treasury curve, and that there will be a general flattening if not an inversion of the yield curve. This is a scenario that would increasingly curb the upward pressure on the US dollar resulting from the interest rate differential and, at the same time, contain the fundamentals-driven downside potential of the US dollar resulting from the expanding twin deficit. Furthermore, the balance sheets of the G4 countries’ central banks are shrinking on the whole, because bond-buying programmes and other measures to bolster the markets are gradually expiring and, in some cases, the funds from maturing bonds are not being reinvested. As a result, the capital markets are generally losing a significant source of support.

Each further interest rate rise makes it more likely that the Fed will pause its cycle of rate hikes due to the strengthening economic headwind from monetary policy. We believe that, in the next few months, the central bank’s interest rate strategy will particularly impact on the short end of the yield curve in the shape of rising or at least steady yields. At the long end, we cannot really see any room for markedly higher yields. Overall, the US yield curve is therefore likely to continue flattening. This is good news for emerging markets that are heavily dependent on financing denominated in US dollars. So it is no surprise that inflows into EM exchange-traded funds (ETFs) have gradually increased again in recent weeks.

Country-specific circumstances necessitate careful security selection

Besides the challenges outlined above, idiosyncratic problems also come into play. In 2018, the price movements of shares and bonds from the different countries presented a much more disparate picture than they had a year or two earlier. In the early summer, for example, Argentina and Turkey came under pressure. Turkey is weighed down by the high level of external debt in the corporate sector, which now stands at over US$ 300 billion. A third of this total is due for refinancing within the next twelve months. Argentina is still battling legacy difficulties and a relatively strong dependency on short-term finance denominated in US dollars. It also needs to implement further structural reforms. Another reason for the high volatility of the EM financial markets last year was the significant number of elections, such as in Brazil.

Emerging markets in a fundamentally good position overall

Despite the current difficult situation, it is important to remember that a number of factors still argue in favour of a long-term investment in the emerging markets. Over the long term, prosperity levels in the emerging markets will draw closer to those of industrialised countries. The sheer number of possible consumers is huge. After all, only a seventh of the global population live in the industrialised countries. It is therefore no wonder that the emerging markets are now the world’s engine of growth. As a result, emerging markets are attracting direct investment from developed markets and have lower levels of government debt.

Details for selected countries

We expect an increasing deterioration in Turkey’s economic situation, which is why we disposed of some assets after the recent bond and currency recovery. Although the central bank significantly raised interest rates – albeit at a very late stage – and thereby successfully counteracted the lira’s depreciation, the political direction under Erdoğan’s leadership remains unpredictable and poses more risks than opportunities for Turkey’s economy. Argentina took strident action against the turmoil in the capital markets and raised interest rates significantly. It also negotiated a bailout with the IMF of US$ 57 billion (the highest payment ever made to support an emerging market) that secures the country’s funding until the end of 2019. But the election scheduled for 2019 could become problematic. The government is under pressure, because Argentina is struggling with very high inflation and thus high interest rates. The peso is therefore likely to depreciate further. The country also has an extremely long list of reforms that it needs to implement in view of past problems, yet reforms tend to take a very long time. There are many indications that Argentina’s – and Turkey’s – economy will slip into recession in the year ahead. By contrast, the situation in Indonesia looks a lot rosier. Not only is it growing, it also has low inflation and a very modest level of external debt.

Brazilian bonds responded positively to the election of Bolsonaro as the new president. We regard the current situation in Brazil as relatively stable. Currency reserves of more than US$ 300 billion give the country a comfortable buffer, although reform policies are standing on shaky ground. The pension system is one area that needs to be reformed. Such reforms always require amendments to legislation, which is why having a majority in parliament is crucial and why Bolsonaro first needs to forge a stable alliance. The country is therefore not among our investment favourites for the time being.

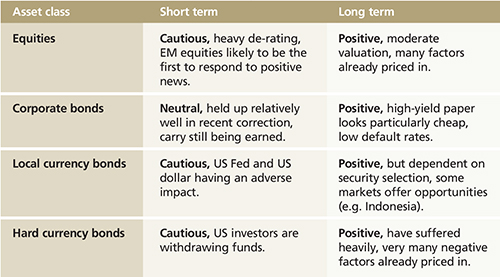

View of the different asset classes

Equities

Until the end of April, EM equities moved in tandem with shares from industrialised countries. From May onwards, however, the continually escalating trade dispute led to greater risk aversion in the markets. Against this backdrop, there was little interest in EM stocks. Measured by the MSCI Emerging Market index, they fell by around 13% in local currency terms over 2018 as a whole. To put that into context, shares from industrialised countries lost a little over 9% in the same period. The correction in some EM equity markets, such as China, even exceeded 20%. We have seen a heavy de-rating of EM equities as a result of the price falls. The price/earnings ratio of shares from the emerging markets now stands at just 11, compared with 18 for US stocks. Current valuation levels are attractive to long-term investors. We advise investors with a shorter investment horizon to wait and see. China’s latest quarterly reporting season was poor. This adverse trend is likely to continue in the first quarter of 2019. Here too, the key questions are whether the Chinese government will react further and whether its economic stimulus measures will have any effect. EM equities were the first asset class to respond very negatively in 2018 and will probably be the first to respond to positive news.

Corporate bonds

Corporate bonds from the emerging markets also offer opportunities. Although coupons in this asset class tend to be lower than for comparable government bonds, corporate bonds fluctuate less. In 2018, the paper was again the least volatile and the most defensive asset class among EM investments. This trend is set to continue for the time being, given that economic conditions are still relatively robust and default rates are comparatively low. We expect EM corporate bonds to hold steady in the months ahead. At present, their default rates do not look set to rise. Kuwait and Poland are among our investment favourites, whereas we are fairly cautious about China and Russia for geopolitical and other reasons. We have also seen a wave of primary market issues in China, take-up of which has not been unreservedly positive of late. Some deals have even had to be called off.

Local currency government bonds

The local currency segment is far more volatile and, unsurprisingly, registered the biggest price fall in 2018. If the Fed continues on its trajectory of interest rate rises, the market environment will remain challenging for local currency paper. Long-term investors are thus more likely to find opportunities in government and corporate bonds denominated in US dollars or euros. Our local currency favourites are Indonesia, the Philippines, Egypt and Nigeria.

Hard currency government bonds

The hard currency bond segment is significantly smaller than its equivalent. EM governments typically begin by issuing bonds denominated in US dollars or euros in order to attract foreign investors. That is why most foreign investors (e.g. from Germany) tend to invest in the hard currency segment. Unusually however, spreads in the hard currency segment have recently widened much more sharply than local currency bond spreads, essentially because they were more heavily affected by outflows. This was primarily a result of the different investor base. US investors, in particular, turned their back on the emerging markets because of the comparatively high yields on US government bonds.

In past crises, we have seen that bonds from the emerging markets often reacted quickly to changes in the wider market but subsequently remained largely stable. Any further losses only occurred at similar levels to those on US Treasuries.

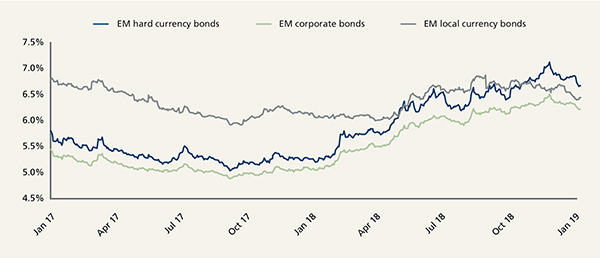

Figure 2: Continuing trend of rising EM yields

Source: Bloomberg, Union Investment, as at 8 January 2019

Summary

Unlike 2018, 2019 will not be a “super election year” in the emerging markets (exceptions: Argentina, South Africa, Indonesia), so relatively little political turmoil is on the cards. The trade dispute and geopolitical stand-off between the US and China will of course remain a factor, although the future direction of travel will be determined soon. The emerging markets are likely to again benefit from the moderate pace of worldwide economic growth in 2019. However, the rate of expansion is expected to be slightly weaker than in 2018 due to the global trade disputes and idiosyncratic country-specific themes (above all in Turkey and Argentina). Increasingly restrictive monetary policy worldwide will probably remain a negative factor for the time being.

We therefore recommend that short-term investors watch the goings-on from the sidelines for now and, depending on their risk appetite, do not yet increase their exposure, or do so only incrementally. After all, volatility is predicted to remain high in the coming weeks. If the US Federal Reserve were to deviate from its course or if the trade dispute were to ease, this would send an upbeat signal that we believe would present a buying opportunity.

Following the widening of spreads in 2018, EM bonds are valued relatively cheaply – particularly in comparison with other fixed-income asset classes – and a good window for investment is already opening up for those with a long-term focus. The same is true for equities. Long-term investors already have opportunities. Overall, however, the divergence among the individual emerging markets is unlikely to go away. This makes careful country analysis all the more important for fund management.

The answer to the opening question of whether it is a good time to invest in the emerging markets following the recent turmoil therefore depends on the individual investor’s investment horizon. Caution is advised in the short term, whereas opportunities have the upper hand from a long-term perspective.

More Related Content...

|

|

|