Beware of the traffic lights

Written By:

|

Simon Hazlitt |

Simon Hazlitt of Majedie Asset Management points out the dangers of a project management approach to investment strategies and the consequences of failing to adequately distinguish between volatility and risk

There’s no denying that the management and oversight of pension schemes has changed dramatically over the last 20 years. In parallel with management developments in the wider world, ever more data and shorter time frames for critical waypoints are used to keep the show on the road. Of course, this in itself is not a bad thing: the prospect of Crossrail being delivered on time and on budget is nothing short of a triumph, attesting to a material improvement in our collective ability to manage these sorts of projects. However, an approach that is suitable for the management of Crossrail can hold dangers if used too readily in the oversight of different kinds of enterprises.

This “projectisation” of management oversight has made itself felt in the pensions world, with The Pensions Regulator (TPR) funding plans, derisking pathways and regular actuarial valuations using less judgement and more data with standardised definitions. Like Crossrail, no one would argue against having more visibility on a plan’s progress in meeting its liabilities, and no member of an investment committee is going to object to greater visibility when, in the case of local authorities, a fund’s outturn will affect a council’s profit & loss statement (P&L). However, it is worth pointing out where such a laudable approach can skew the way a plan undertakes its investment strategy, leading to potential problems in the long term. One of the main shortcomings of the “traffic light” approach is to manage things with ever greater frequency. This works well in the strict project, as to catch an execution problem or an overspend early, is to nip it in the bud. With something more uncertain, like the management of an investment portfolio, such an approach can have some less desirable consequences, all of which we can see in today’s markets. In turn, we’ll look at how this affects (and oversimplifies) our collective understanding of risk, how such an approach can lead to potentially crowded uniformity and where valuations can take leave of fundamentals. Finally, it can lead to changes in behaviour which could, at the margin, lead to political risk.

Much is written about risk, but it seems to us that it’s still very poorly understood. Part of the problem is that most people’s deep-seated desire to quantify things, to have a number to look at, and quote to clients, can feel very reassuring. If something can be expressed as a number, it seems less scary and more controllable: just minimise that number and you’ll be fine. The issue is that some phenomena are not easily expressed as numbers, or at least not as a single number. They are too complex, too interlinked, too reflexive to be boiled down to a solitary figure. The desire to quantify something that doesn’t suit easy quantification forces people to make questionable choices, chief amongst which is using volatility as a proxy for risk.

Volatility is not the same as risk

Risk does not have a clear numerical meaning. Is it the probability of loss? Is it the magnitude of possible losses? Does it refer to losses that can be recovered from, or only those which are permanent? This ambiguity means that most people, when talking about risk, actually end up talking about volatility instead. Volatility is just a measure of how much something moves around – basically it’s a measure of noise – and so it’s fairly easy to represent it with a number. The assumption implicit in all mainstream analysis is that volatility is a good proxy for risk and that things which are more volatile are therefore more risky. Thinking about this for a little while shows that it is at best an oversimplification, and at worst, completely untrue. Lots of things can be very volatile, without being particularly risky in the longer term – an example would be government tax receipts. They can fluctuate substantially in the short term as booms and busts come and go, but in the long term they generally rise, as inflation and economic growth combine to boost takings gradually. The underlying trend is not very risky at all – in fact it’s very predictable.

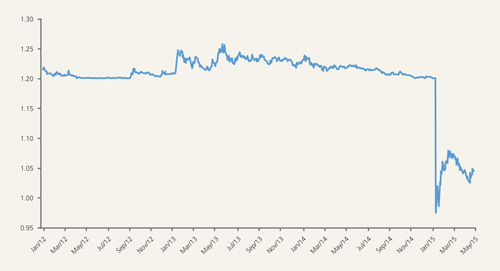

Conversely, things that appear very stable, with very low volatility, can turn out to be extremely risky. Figure 1 shows the euro/Swiss franc exchange rate from the start of 2012 until May 2015. For the period up until the 15 January 2015, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) had pegged the value of the franc to the euro, keeping the exchange rate in a very narrow band between €1.20 and €1.25, or about +/- 2%. With volatility as low as that, investors began to regard the exchange rate as a stable, low-risk benchmark. Many people started to lever up bets using the pair – after all they never moved very much, and so it was “safe” to add on a lot of other risks. This all changed when the SNB announced, unexpectedly, that it would no longer maintain the peg, causing the Swiss franc to appreciate by almost 30% against the euro in a matter of minutes. Many traders were wiped out entirely – and some specialist currency brokerages, like Alpari, went bust. Even Citigroup and Deutsche Bank, massive organisations with advanced risk control functions, each lost about $150 million, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Figure 1: Euro/Swiss franc exchange rate

Source: Bloomberg

Volatility was plainly a very poor proxy for risk in this case. The big risk in the euro/Swiss franc exchange rate was always that the SNB might decide to abandon the peg. Only by analysing the situation carefully, and making a judgement about the SNB’s ability and desire to continue the peg, could a sensible conclusion about risk be reached.

Volatility also tells you nothing about the risk of long-term, gradual underperformance. It’s possible for a stock with very low volatility, which superficially would be viewed as “safe”, to gently underperform the market year after year. It may not “blow up” at any point, but the end result is the same. Coca-Cola, which is by most measures one of the least volatile stocks in the S&P 500 Index, has lagged the market by 44% since its relative peak in 1997, and by 10% in the last five years. It might be easy to sleep at night if you own it, but returns have been poor.

Crowded uniformity

Another consequence of the “project” approach is the tendency to navigate by the risks seen in the near future, success being the degree to which these are mitigated. This of course is vital when managing a construction undertaking, but can have consequences in the investment arena. As discussed above, volatility is often seen as a proxy for risk, not least because it is easy to quantify and it is also a good substitute for uncertainty, a direct import from project management 101, where uncertainty can lead to time and budget overrun. Uncertainty is also a threat to those professionally engaged to advise on investment strategy: when asked for a view, it is simply not good enough to express a judgement, or to say “I don’t know”. Volatility in these circumstances can wreak havoc with the traffic lights, leading to questions as to the effectiveness of the whole “plan”. Thus advice will naturally tend towards what is more certain, even if returns from such advice are modest. This approach holds two dangers for the long-term investor.

The first danger is that a strategy that seeks only modest returns for fear of disappointment is a self-fulfilling one. One obvious point to make is that a long-term portfolio’s progress will always be mixture of gains and losses, the skill being to minimise the latter and maximise the former. If the former cannot be maximised due to a desire for certainty in the short term, then the portfolio’s sensitivity to loss is heightened, feeding the original fear of uncertainty, and so hobbling the portfolio’s return potential, and so on.

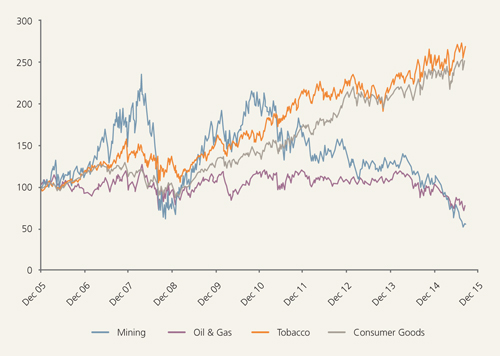

The second danger is that, as the risks perceived by all such investors are essentially the same (areas of uncertainty where prices go up and down a lot), so the strategies employed to mitigate such risks are pretty similar. We can see that in investment markets today, where bonds cling onto bubble valuations, and those equities that most resemble bonds are almost two standard deviations above historical valuation levels. Figure 2 above depicts four sectors in the UK stockmarket showing a remarkable bifurcation, highlighting the premium that investors currently attach to those sectors like tobacco that exhibit low volatility. Swiss franc, anybody?

Figure 2: Share price divergence opens valuation gap

Source: Bloomberg

We can also see this preference for certainty in the fortunes of the fund management firms and products in the market today. In the ascendancy are those firms and strategies that scratch this particular itch: formulaic approaches that minimise judgement and maximise structure, alighting on investments least likely to surprise. Given the weight of money flowing in from investors, this has been a self-fulfilling phenomenon, and it now exposes investors to a risk that is oddly overlooked, that of valuation.

Political risk

One consequence of the dash to surety in the pension world is to exchange risk-seeking activities for rent-seeking ones. Thus equities are being sold in favour of secured lending, and infrastructure. This represents the next step for schemes in their search for visibility. Having ditched “risky” (volatile) equities for those with more certain prospects, the natural progression is to avoid the risk of value creation altogether, and simply seek a rent from those that do. We have been surprised here at Majedie at the lack of public discussion over the risks to these sorts of activities (and have written on the subject), but we’ll touch on one in particular that seems to have received no airtime and is very relevant to public sector schemes.

Conclusion

By changing from the incubator of the next generation’s value creation to its turnpike, the role of the pension fund in the intergenerational exchange alters, and none too subtly. Of course the pension fund will argue that the provision of loans in the absence of banks, or the financing of much-needed infrastructure in times of government budget cuts, are vital public services. To the generation denied remotely affordable housing, saddled with those budget cuts wrought by historical overspend and an astonishing determination to shield pensioner handouts, it might perhaps look a little different.

More Related Content...

|

|

|