Can an investor really have “impact” in the public markets?

Written By:

|

Martin Grosskopf |

|

Hyewon Kong |

|

Jonathan Lo |

Martin Grosskopf, Hyewon Kong and Jonathan Lo of AGF Investments look at how asking the right questions can help investors determine if their investment is making an “impact”

Over the last 10 years, there has been a dramatic change in how institutional asset owners, such as pension plans and foundations, view sustainability issues such as climate change. 2015 stands out as a year that demonstrated the materiality of sustainability, which had previously been considered interesting but vague.

Governments around the world have agreed to take meaningful measures to reduce greenhouse gases entailing an energy and land use transition that will take decades to play out. Sectors such as automotive and coal have witnessed severe declines as they have proved to be on the wrong side of tightening environmental regulations. These issues have heightened investor awareness of the risks associated with transitioning to a more sustainable economy.

Equally important has been the rise in investor desire to have influence or impact this change – in other words to seek out opportunities and accelerate change as much as minimise the risk. Although historically investors used the term impact synonymously with community investing with a focus on private and local investments, it is now being more broadly applied to include certain categories of publically-quoted funds. Whether or not this is a useful evolution of the concept is open to debate. We believe that some funds are designed to influence and impact the flow of capital in favour of sustainability solutions and that while they differ in approach and focus they have some characteristics in common. Our purpose here is to identify these.

One question we hear often is “how do I know if your strategy really has impact?” We believe that truly impactful portfolios have several common characteristics. The following questions are ones that we believe investors should ask in determining whether their investment portfolio is making an impact.

Is it off-benchmark?

After years of discussing climate change, the difficulty now for most institutional investors is not in defining the risk, but instead determining what to do about it within generally accepted investment parameters. These parameters view conventional benchmarks as arbitrators of what is reasonable from a risk/return perspective. Deviations from benchmark (meaning active investments) need to pay off relatively quickly to justify the additional risk taken. This constraint ensures that the bulk of public market allocation is either invested passively (which does not distinguish between companies’ business models) or through benchmark-optimised active strategies. In either case, the resulting financial products are quite obviously not designed to transition away or towards anything. They are designed to provide some semblance of predictable financial behaviour and marketability.

We believe impact investing should actively seek to invest in companies that have the potential to create positive economic, environmental and social impact. Thus, funds that are impact-focused within the public markets rarely look much like conventional benchmarks and therefore have very high active share. As a result, they tend to show higher volatility, an attribute which is also reflective of a portfolio construction process that maximises exposure towards sustainability themes.

Does it have a rigorous thematic approach?

For economies to become more carbon efficient and sustainable (meaning reduced energy intensity, emissions, water use, etc.), companies need to invest in new technologies and processes that can enable this transition. These innovations require long-term capital to develop and penetrate the market – in effect, risk capital or what can be called impact capital.

In fact, a transition to a low-carbon economy requires investors who are willing to allocate towards those firms with the most attractive solutions for pressing environmental issues. Thematic investing requires that investors have a well thought-out process for defining a universe of companies engaged in providing solutions and selecting the most appropriate investments for a portfolio. The portfolio would be optimised for exposure to the themes and financial characteristics, with both having importance. These funds assume that a transition is occurring and will be positioned to benefit from it – they are not simply hedging their fossil-fuel exposure.

We have found that there are few truly thematic strategies in the global investment management industry. Approaches that use engagement or ESG integration are far more common, but are limited in their impact in that they do not solve the tension between short-term investor or management objectives and longer-term impact. One can be an engaged or responsible investor and still justify new investments in fossil fuel infrastructure as prudent within an overall portfolio. Not all investors will view it as their role to consider the longer-term impact of these commitments on environmental policy objectives.

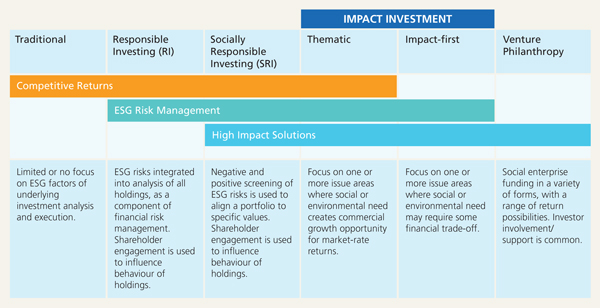

Figure 1: Impact investment spectrum

Source: MaRS ‘State of the Nation: Impact Investing in Canada’, 2014

Is the strategy taking fossil-fuel exposure seriously?

Although obvious, it is difficult to have impact by being invested in the very source of the problem that one is trying to transition away from. Investing in (and thereby improving the cost of capital for) solutions providers entails a reduction in the weight elsewhere – logically from the most problematic sectors.

There are arguments made that selling any fossil-fuel company simply passes the shares on to less responsible actors. However, some sectors are justifiably allocated away from due to their poor fundamentals, with coal being the latest example. Even the coal companies themselves have begun to disclose the divestment movement as a material risk to their cost of capital, indicating that new investors are not necessarily willing to backstop environmentally disadvantaged business models.

Clearly, many strategies will view the transition period as being quite long and will look to maximise their cash flows from fossil fuels while they have the opportunity – these are not likely to be of interest to impact investors.

Does it publish a broad set of environmental data?

Measuring the environmental impact of a portfolio is in its infancy relative to measuring its financial characteristics. The data is reported differently by many companies, even within the same sector and its robustness can be questioned given the lack of third-party validation.

Despite these challenges, it is possible to collect data that gives a directional indication of the portfolio’s environmental impact. Reporting on single-factor issues such as carbon emissions is likely to be an early step – but more important is an overall sense of the portfolio’s environmental footprint, which will include other important factors such as water use, land management, toxic emissions, etc. This broader data set is also increasingly useful for ongoing engagement with companies as even the most attractive solution provider will still have improvements it can make to its own manufacturing footprint.

Does the investment team have specialised expertise?

Establishing the credibility of the investment team is of no less importance for sustainability-focused funds than for other investment products. In fact, we would argue that a strong background in both financial and environmental analysis is important for developing a robust process that can critically assess the various sources of data received – ESG research firms, sell-side reports, company disclosures.

Individuals with both strong financial backgrounds and strong environmental skills are very difficult to find. This is a skill set that is now being promoted within many MBA programs but has only become popular in the last few years. For funds with a longer tenure, expect to find environmental specialists who developed the appropriate financial skills later in their education or career. Most individuals with an early financial specialisation do not have the technical knowledge of environmental issues to dig deeply into this side of the investment decision.

Is the “sustainability” of financing a focus?

While many institutional investors recognise some opportunity within emerging sectors, such as renewable energy or battery storage, they often pursue these investments through private financing. Ultimately, however, most renewable projects are destined to be priced and owned in the public markets to satisfy the defined exits periods for private capital. Public markets are also, by definition, more participatory and reflective of a broader range of investors. Upstream and downstream markets depend on each other over time – both are essential if any low-carbon transition is to occur.

Large institutional investors usually have access to private equity opportunities that have inherently lower volatility as they are not subject to the public market price fluctuations, which are more pronounced in the emerging sustainable sectors. As a result, the players in the public equity sustainable sectors are more likely than not dominated by hedge funds and day traders with shorter-term incentives.

The success of many of the transition technologies will depend on the active involvement of patient, long-term capital within the public markets. An impact strategy should show awareness of its role within the financing ecosystem.

Does the investment manager have a history of moving the bar forward?

The sustainable investment industry is still evolving rapidly as the products and processes adapt to changing trends and new priorities. Firms that are focused on having impact have usually been involved in industry associations and research initiatives over many years as they strive to add to the base of knowledge in the industry and strive for continuous improvement.

Has the fund a demonstrated tenure?

True commitment to sustainable investing requires firms to support their products during periods of poor performance or lack of interest. Too many times, over the years, firms have launched products with an impact or sustainability focus only to close them quickly if they do not immediately reach or are unable to maintain hurdle rates. Naturally, the logic is to make short-term financial targets but the nature of these products is longer-term. The need for firms to reallocate capital to the highest returns should be balanced with the need to nurture a sustainability product in a too-often fickle market.

1. Does not provide investment advice or recommendations

More Related Content...

|

|

|